Introduction

In his article, ‘Weaknesses in the supply chain: who packed the box?’, Hesketh (2010) highlights the marked contrast between the regulatory scrutiny of passengers’ baggage and that of containerised cargo destined for export:

Imagine arriving at an airport to board a flight. You approach the check-in desk. You are asked the normal questions about your baggage. But consider the consequences of giving some not-so-normal answers. You have never seen the bag you are carrying; you did not pack it and you have only been told what is in it. It is unlikely you would be allowed on a flight. There are strong similarities between this and how we manage information about cargo moving along the international trade supply chain.[1]

Hesketh proceeds to explore strategies to address this anomaly and identifies options designed to provide regulators and other members of the trading community with accurate, timely and reliably sourced information on internationally traded goods at all points in the supply chain.

One may wonder why it has taken so long for customs authorities to focus on such fundamental matters. After all, the potential transport security risks associated with both passengers and cargo and the consequent need for enhanced security measures have for decades been recognised and addressed by both the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) and the International Maritime Organization (IMO).

So why have customs authorities overlooked this seemingly obvious need until relatively recently? The answer can be found in the national (and, ultimately, international) cross-border policy imperatives of the day. In this regard, it is pertinent to note that safety and security have been long-standing priorities for transport authorities, whereas the principal focus of Customs has traditionally been revenue collection and trade compliance. And whilst the majority of regulatory responsibilities may be managed by way of more traditional compliance management methods, it is essential for security risks to be dealt with through prevention rather than detection, ideally at the point of origin. Put simply, an administration’s priorities are set by its political masters, and national security has only recently been identified as a priority for Customs.

National cross-border policy imperatives can usually be ascertained from the economy’s ministerial or departmental structure; and specifically from the location of the customs administration within that structure. Generally speaking, a country that identifies import revenue and other trade-related matters as high national priorities will locate its customs administration within its finance, revenue or trade portfolio, a practice that is commonplace among most developing and least-developed economies. In Namibia, for example, the Directorate of Customs and Excise, which is responsible for collecting some 85 per cent of the country’s tax revenue, forms part of the Finance Portfolio. Similarly, the Royal Customs and Excise Department of Brunei Darussalam is responsible for collecting 98.7 per cent of total revenue, and is unsurprisingly located within the Ministry of Finance.[2]

However, in those countries where import revenue is decreasing in relevance and national security is emerging as the principal cross-border concern, the customs administration is likely to form part of a border protection or homeland security portfolio (Widdowson, 2007). This is an increasingly common phenomenon among developed countries. In the United States (US), for example, US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) form part of the US Department of Homeland Security; in Canada the customs responsibilities are administered by Canada Border Services Agency, which forms part of Public Safety Canada; and in Australia the policy and operational arms of Customs form part of the Department of Immigration and Border Protection and the Australian Border Force respectively, both of which fall within the federal Immigration and Border Protection portfolio. While not the focus of this paper, it is contended that this trend will soon become prevalent among other developed economies, particularly in light of the current immigration crisis and associated border protection concerns in the European Union (EU) and other regions of the world.

Trade facilitation: the initial catalyst for change

The way in which customs authorities have traditionally performed their role over the centuries can best be described as an interventionist approach, often manifested by regulatory intervention for intervention’s sake. However, the latter part of the 20th century saw a change in approach to one which recognised a need to balance regulatory intervention with trade facilitation, due to the mounting pressure from the international trading community to minimise government intervention in commercial transactions. The advent of the global marketplace and the technological advances that have revolutionised trade have further fuelled the momentum of the global trade facilitation agenda and have led to a regulatory philosophy of ‘intervention by exception’, that is, intervention when there is a legitimate need to do so, based on identified risk.[3]

Consequently, more than two decades prior to the terrorist events of 11 September 2001 border management agencies were already screening international cargo prior to its arrival (but rarely prior to exportation) not for security reasons but for the purpose of facilitating the movement of legitimate trade. By ensuring that consignments complied with trade regulations, Customs and other authorities were able to streamline clearance processes, thereby providing the international trading community with greater certainty, and consequently reducing the regulatory cost of trade.

The desirability of pre-screening and pre-clearance is outlined in various elements of international trade law, including the International Convention on the Simplification and Harmonization of Customs Procedures, as amended (1999) (also known as the Revised Kyoto Convention); the WCO’s Immediate Release Guidelines (WCO 2006) and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT, 1994).

In more recent times, the importance and benefits of pre-clearance have been highlighted by the World Trade Organization (WTO) in its Agreement on Trade Facilitation (WTO 2013), which represents a Protocol of Amendment to GATT, 1994, and which is expected to be ratified in mid-2017. Article 7 of the Agreement, which relates to the release and clearance of goods, provides as follows:

1. Pre-arrival Processing

1.1 Each Member shall adopt or maintain procedures allowing for the submission of import documentation and other required information, including manifests, in order to begin processing prior to the arrival of goods with a view to expediting the release of goods upon arrival.

1.2 Each Member shall, as appropriate, provide for advance lodging of documents in electronic format for pre-arrival processing of such documents.

This principle reflects the provisions of the Revised Kyoto Convention, which was drafted in 1999 and entered into force in 2006, including Standard 3.25 which provides that ‘National legislation shall make provision for the lodging and registering or checking of the Goods declaration and supporting documents prior to the arrival of the goods’. Importantly, such measures are purely voluntary, and are made available to those members of the international trading community who wish to take advantage of pre-arrival processing procedures in the interests of facilitating the clearance of their goods.

National security: a new imperative

Following the terrorist attacks of September 2001, regulatory intervention in cross-border trade increased globally as supply chain security emerged as the new international imperative.

In early 2002, the ICAO introduced additional measures to further mitigate aviation security risks. Its Plan of Action for Strengthening Aviation Security includes a global audit program to ensure that security standards are being properly implemented, and the organisation has pointed to ‘myriad security measures implemented by states, enforcement agencies, airport authorities and other concerned parties since the events of 11 September 2001 [that] thwarted acts of unlawful interference that would otherwise have been successful in weakening the integrity of international civil aviation’ (ICAO 2007, p. 10). Of particular relevance to the current topic, the standards that have been introduced by the ICAO serve to identify the necessary security controls to be applied to all cargo and mail items prior to loading onto a commercial flight in order to mitigate the associated risks. In a joint examination of regulatory approaches to air cargo security, ICAO and the World Customs Organization (WCO) agree that:

A global secure supply chain approach to air cargo and mail could be achieved by applying security controls at the point of origin. The implementation of the secure supply chain is an efficient solution, built on a risk-based approach that meets the following objectives:

-

respect existing obligations of businesses operating in the air cargo supply chain;

-

share costs and responsibilities among all stakeholders and allow cargo to be secured upstream in the supply chain to reduce the burden of security controls imposed on aircraft operators;

-

facilitate the flow of cargo transported by air and reduce or limit possible delays generated by the application of security controls;

-

apply appropriate security controls for specific categories of cargo that cannot be screened by the usual means due to their nature, packaging, size or volume; and

-

preserve the primary advantages of the air transport mode: speed, safety and security (ICAO & WCO 2013, p. 8).

Similarly, the IMO developed the International Ship and Port Facility Security Code (ISPS Code) which prescribes mandatory security management requirements for ports and ships. The ISPS Code was adopted as an amendment to the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS)[4] in 2002, and entered into force in 2004.[5] The objectives of the Code are:

-

to establish an international framework involving co-operation between Contracting Governments, Government agencies, local administrations and the shipping and port industries to detect security threats and take preventive measures against security incidents affecting ships or port facilities used in international trade;

-

to establish the respective roles and responsibilities of the Contracting Governments, Government agencies, local administrations and the shipping and port industries, at the national and international level for ensuring maritime security;

-

to ensure the early and efficient collection and exchange of security-related information;

-

to provide a methodology for security assessments so as to have in place plans and procedures to react to changing security levels; and

-

to ensure confidence that adequate and proportionate maritime security measures are in place.[6]

From a Customs perspective, the terrorist attacks of 2001 resulted in a sharp reversal of the balance between trade facilitation and regulatory intervention to which many governments had been aspiring. In the wake of these events, the US borders immediately closed to international trade, and the international approach to border management changed significantly. This included the introduction of a broad range of national and international initiatives, led by the US, designed to ensure the safety and security of global supply chains. One of the principal methods of addressing the newly perceived security risk of terrorist intervention in the international supply chain was the deployment of US personnel to foreign seaports to identify and examine high-risk cargo destined for the US prior to loading. The initiative, known as the Container Security Initiative (CSI), is now operational in 58 ports throughout the world (USCBP 2016). This and other security-driven initiatives saw CBP conceptualising its ‘border’ in a new way. As noted by Bersin (2012, p. 392):

The unacceptable economic and political consequences of shutting down the border, coupled with the new security imperative, forced a fundamental shift in our perspective. We began to understand that our borders begin not where our ports of entry are located, but rather, where passengers board air carriers and freight is loaded on maritime vessels bound for those ports of entry.

Another strategic element of CBP’s layered cargo security strategy was the introduction of mandatory advance reporting of containerised sea cargo. Commencing in the US, the initiative has spread rapidly to other major trading countries. It involves the electronic reporting of cargo, usually by the carrier, to the customs authority in the importing country for the purposes of advance risk analysis prior to its arrival in the country of destination. In the case of cargo bound for the US, the transmission is required 24 hours prior to the container being loaded onto the vessel. The initiative has since been extended to other modes of transport, including air in some countries.[7]

The US initiative, known as the Advance Manifest requirements, but commonly referred to as the ‘24 hour Rule’, has been operational since 2003 for maritime container cargo, and the advance reporting of manifest data has since been phased in for other transport modes.

In addition, the Importer Security Filing (ISF) rule under the US SAFE Ports Act (commonly referred to as the ‘10+2 Rule’), has been in operation since 2009, requiring traders to make advance declarations to CBP in respect of import cargo arriving in the US by vessel.[8] The US has also been developing its Air Cargo Advance Screening (ACAS) initiative, which requires the provision of pre-departure electronic data for destination country analysis prior to aircraft departure. A voluntary pilot program is currently being conducted in which participants provide CBP with advance air cargo data at the earliest point practicable prior to loading cargo onto an aircraft that is destined to or transiting through the US.[9]

Following the US lead, the WCO identified the need to develop international guidelines to provide its members with uniform strategies to secure and facilitate global trade. The result is the WCO SAFE Framework of Standards to Secure and Facilitate Global Trade (SAFE Framework), which was first introduced in 2005 and has undergone several iterations since that time, the latest being the 2015 edition, which was endorsed by the WCO Council in June 2015 (WCO 2015). Along with other significant principles and standards,[10] some of which are discussed later in this paper, the SAFE Framework reinforces the need for and benefits of advance cargo reporting, and encourages the screening of containerised cargo prior to its loading onto the vessel.

Advance manifest requirements: implementation analysis

Although advance manifest requirements are in their infancy for air cargo, the global introduction of such requirements for containerised sea cargo is more mature, and while it is widely recognised that the practice is spreading fairly rapidly, the extent and speed of global implementation is not yet fully appreciated. The current study was triggered by the realisation that this fundamental change in practice by Customs, and its consequential regulatory impact on the trading community, is becoming commonplace.

The research examines two particular elements of advance manifest implementation in relation to containerised sea cargo:

-

the manner in which the policy has been adopted and applied by individual economies

-

the proportion of containerised sea cargo impacted by its adoption.

The data were obtained through a comprehensive review of government websites and databases, supplemented by a review of information provided by service providers involved in the cross-border movement of cargo. The percentage share in total world imports of merchandise for individual economies was derived from the WTO International Trade Statistics series, based on imports for the year 2014. This measure includes modes of transport other than sea, as well as bulk and break bulk (or general) sea cargo. However, its use is considered to be appropriate in deriving an acceptable estimate of an economy’s share of global containerised sea cargo.

Policy variations

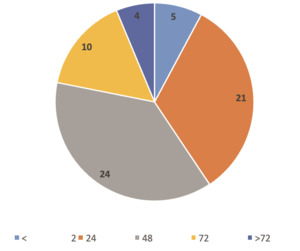

The manner in which individual countries have adopted the policy of advance manifest reporting varies considerably. For the purposes of this research, the variations have been categorised according to the timeframe in which the cargo manifest is required to be submitted to the customs administration in the country of destination (see Figure 1).

Category A has the earliest timeframe, and reflects the requirement of some administrations for cargo manifests to be submitted prior to loading the container onto the vessel. This approach enables Customs in the destination country to prevent high-risk containers from being loaded.

Category B requires the cargo manifest to be provided prior to departure of the vessel from the port of export. However, in cases where the cargo is in fact reported prior to loading the container onto the vessel, Customs in the country of destination has the opportunity of preventing high-risk containers from being loaded. In those cases where the cargo is assessed as being high-risk following the vessel’s departure, Customs will prevent the container from being unloaded at the destination port.

Category C requires the cargo manifest to be submitted prior to the arrival of the vessel in the country of destination, which enables Customs in the importing country to prevent high-risk containers from being unloaded. Category D applies to those countries that have no advance manifest reporting requirements, and allows for the cargo to be reported to Customs within a specified timeframe following its arrival.

The research has identified 101 countries with advance cargo manifest requirements in place, that is, Category A, B and C (Figure 2):

-

Those countries with Category A requirements include the US, Mexico, the 28 members of the EU, Norway, Switzerland, Turkey, China, Canada and Nigeria. All Category A countries require cargo manifests to be submitted 24 hours prior to loading the container onto the vessel.

-

Only one country, Japan, has introduced Category B requirements. It requires the cargo manifest to be submitted 24 hours prior to departure of the vessel from the port of export.

-

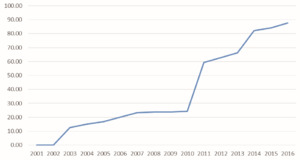

The remaining 64 countries require the cargo manifest to be submitted prior to the arrival of the vessel in the country of destination. Timeframes generally vary between 24 and 72 hours, although some have reporting times as low as five hours (for example, Taiwan), and at the other extreme, Benin requires manifests to be submitted 7 days prior to arrival (see Figure 3).

It should be noted that some countries have different reporting requirements for specific trading partners. For example, Mauritius requires that cargo arriving from its close neighbour, Reunion Island, should be reported no later than five hours prior to arrival, whereas cargo arriving from elsewhere is to be reported no less than 24 hours prior to arrival. In such situations, the higher figure has been used in the context of this analysis.

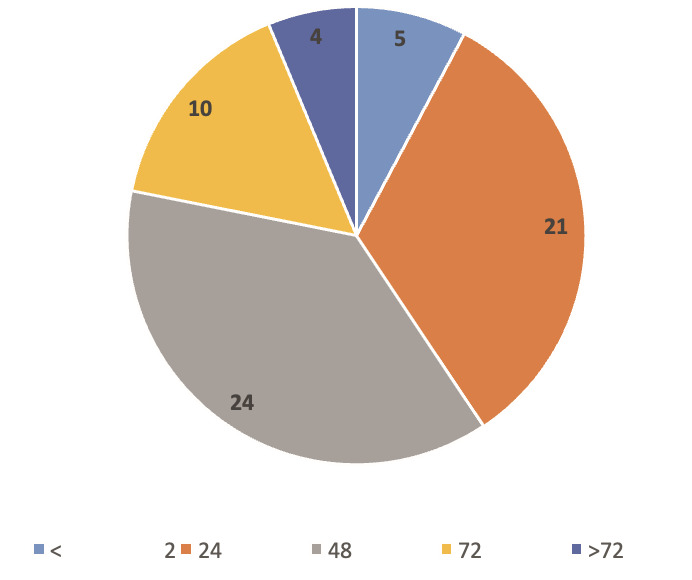

By weighting each country by its percentage share in total world imports of merchandise,[11] it was estimated that 63 per cent of imports globally are subject to Category A requirements, 4 per cent to Category B requirements, 21 per cent to Category C and 12 per cent to Category D[12] (Figure 4).

Proportion of containerised sea cargo subject to advance reporting

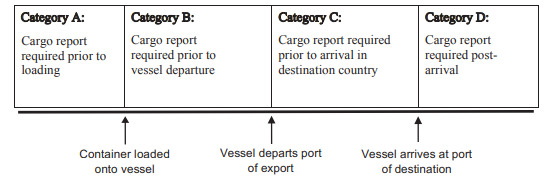

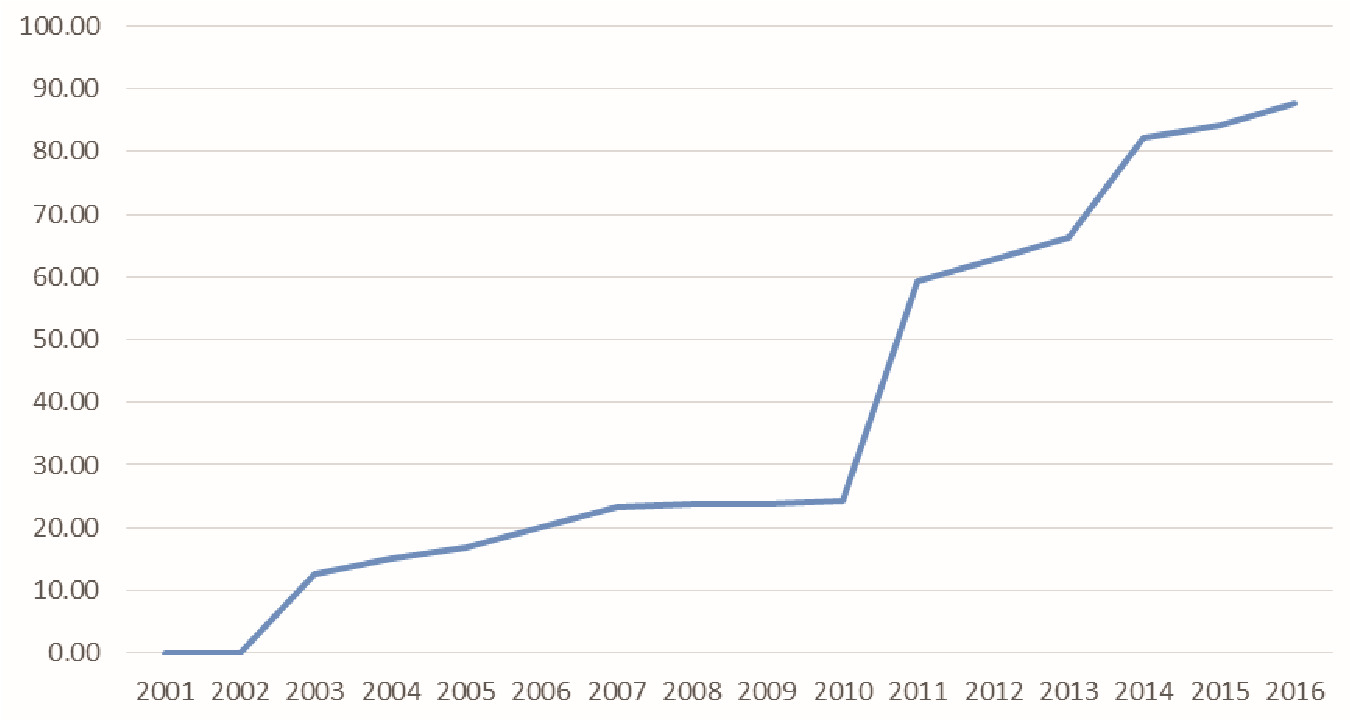

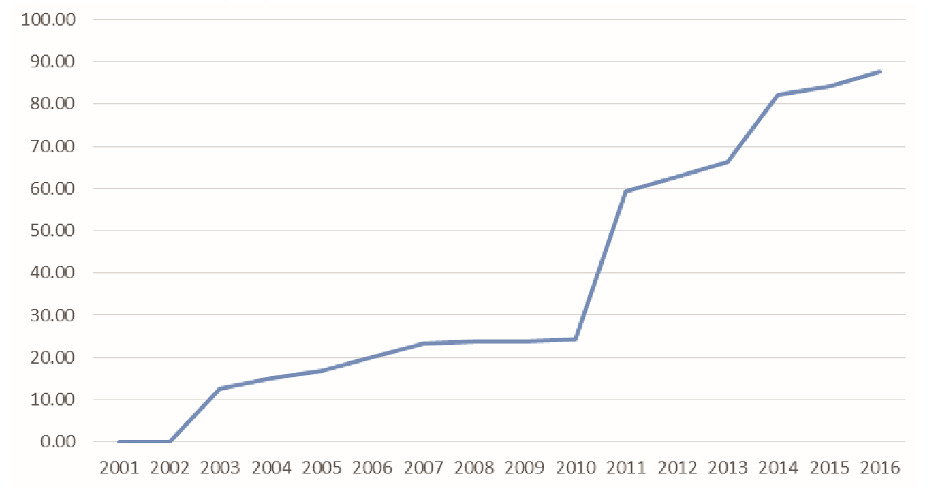

Figure 5 serves to demonstrate the rapid adoption of advance manifest requirements since their initial introduction by the US in 2003. Similarly, Figure 6 shows the percentage of containerised sea cargo imports globally that are subject to advance reporting requirements. From a zero base immediately following the 2001 terrorist attacks, an estimated 87.68 per cent of such cargo is now subject to Category A, B or C reporting requirements.

The sudden rise in such requirements in 2011 that is evident in Figures 5 and 6 is due to the EU’s implementation of the requirement to report cargo 24 hours prior to its arrival at an EU port, with effect from 1 January 2011.

It is likely that other countries will follow, especially since the requirement for advance electronic cargo data reporting is enshrined within the SAFE Framework. In this regard, future implementation is already being planned in countries such as South Africa and Korea, both of which intend to introduce Category A requirements.[13]

Such reporting requirements are in addition to pre-existing advance reporting requirements set by other border management agencies, such as in the US where the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) sets additional advance reporting requirements for food exports to the US by reference to the Bioterrorism Act (2002). In many countries advance reporting to sanitary and phytosanitary authorities also applies, although these requirements often predate 2003 and are generally concerned with ensuring that adequate inspection staff are available to clear the goods on their arrival.

Trusted traders

In an effort to restore a degree of normality and predictability for legitimate traders following the effective closure of the US borders in September 2001, the international trading community worked closely with CBP to introduce more facilitative arrangements for those who could demonstrate a high level of security across their supply chains. The resultant program, known as the Customs-Trade Partnership Against Terrorism (C-TPAT) represents another element of CBP’s security strategy. It provides authorised traders with streamlined clearance procedures, greater certainty and formal recognition of their ‘trusted’ status in return for achieving and maintaining jointly (CBP and industry) developed security standards.

Recognising the benefits of such a scheme, the WCO included in its SAFE Framework a set of guidelines upon which its members could develop national arrangements that reflected the US C-TPAT initiative and which, importantly, could be formally recognised by other member administrations. Among other things, the SAFE Framework provides guidelines for formally recognising and providing benefits to trusted traders, known as Authorised Economic Operators (AEO) as well as mutual recognition guidelines. An AEO is a member of the international trading community that is deemed to represent a low customs risk and for whom greater levels of facilitation should be accorded, and where two countries have a Mutual Recognition Agreement (MRA) in place, an entity’s AEO status should be recognised by the customs administrations of both economies. A number of MRAs have already been negotiated, and the benefits of such arrangements are now being realised. For example, under the agreement between New Zealand and the US that provides for mutual recognition of New Zealand’s Secure Export Scheme and the US C-TPAT program, goods exported to the US by traders who are members of Secure Export Scheme are 3.5 times less likely to be held up for examination upon arrival at a US port (NZCS 2013).

Unlike the C-TPAT program, the 2007 and subsequent iterations of the SAFE Framework expand the criteria for an AEO to include trade compliance as well as supply chain security. Such criteria go well beyond the security agenda which originally triggered the development of the SAFE Framework, and have introduced an additional layer of complexity to its administration. However, as noted by the then Secretary General of the WCO when responding to questions about the intended coverage of the original (2005) version of the SAFE Framework:

From a Customs perspective, a participant’s reliability history and consistent adherence to basic Customs requirements, even outside of the security context, is so fundamental as to form the foundation for all special programme participation. This is especially true when considering programmes with a security emphasis, such as SAFE.[14]

The AEO guidelines that were subsequently issued by the WCO go to great lengths to emphasise this point.[15] The AEO concept has more recently been adopted by the WTO in its Agreement on Trade Facilitation. Article 7, ‘Trade Facilitation Measures for Authorized Operators’ provides that:

Each Member shall provide additional trade facilitation measures related to import, export or transit formalities and procedures … to operators who meet specified criteria, hereinafter called authorized operators. Alternatively, a Member may offer such facilitation measures through customs procedures generally available to all operators and not be required to establish a separate scheme … The specified criteria shall be related to compliance, or the risk of non-compliance, with requirements specified in a Member’s laws, regulations or procedures.

Importantly, assessment of a trader’s eligibility for C-TPAT membership, AEO status and participation in related programs involves a review of their entire supply chain including relevant aspects in the country of exportation. In this way, the customs administration in the country of importation can make an assessment of the trader’s practices, procedures, personnel, systems and commercial arrangements, and whether they are likely to pose a risk from either a trade compliance or supply chain security perspective. Ideally, mutual recognition arrangements between trading partners would ultimately enable those aspects of the trader’s supply chain to be verified by the customs administration of the exporting country. However, it is considered that the associated degree of trust in a trading partner’s regulatory capability that is required for mutual recognition arrangements to operate effectively will inevitably restrict the practicability of such mechanisms.

Further, the lack of regional or multilateral mutual recognition arrangements has the potential to lead to an unwieldy number of MRAs. Consider for a moment what it would mean for the 180 WCO members if each had an AEO program in place and mutual recognition was to be achieved across all such programs. First, it is necessary to take into account the fact that the 28 Member States of the EU have established a single AEO program. The EU has accomplished this by reaching internal agreement among its members on the way in which the SAFE Framework should be interpreted and applied, resulting in a single EU AEO scheme, albeit with some national variations in practice. This has eliminated the need for its trading partners to engage in bilateral negotiations with individual EU Member States, effectively reducing the potential number of ‘national’ programs from 180 to 153. Consequently, the number of bilateral agreements that would need to be struck in order to achieve mutual recognition among all WCO members is 11,628, with each country being involved in the negotiation of 152 individual agreements. Accepting that trade does not occur between all WCO member countries, the magnitude of the remaining bilateral agreements would not only place a burden on the administrators charged with negotiating and maintaining the agreements but also the international trading community faced with such a proliferation of administrative procedures (Widdowson, 2014).

This is an important point to consider, given the commonly held view among commentators that the principle of mutual recognition is fundamental to the effective operation of the AEO program. For example, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) highlights the importance of achieving mutual recognition from the perspective of developing economies:

In the longer term, mutual recognition of AEO status will be critical to ensure that operators who comply with the criteria set out in the SAFE Framework and have obtained AEO status in their own country are in fact able to enjoy the benefits outlined in the SAFE Framework and may participate in international trade on equal terms. In the absence of a system for global mutual recognition of AEO status, traders from some countries, particularly developing economies, may find themselves at a serious competitive disadvantage (UNCTAD 2008, p. 111).

A similar view is expressed by the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC):

ICC has maintained that achievement of a mutual recognition process for companies implementing the Framework procedures is a top priority. Mutual recognition is necessary to capture the trade benefit of a world standard for security and trade facilitation, i.e., that:

-

A supply chain partner accepted as an AEO by a customs administration that participates in the Framework will not be subject to multiple verifications of its status by participating Administrations or other AEOs, i.e., that an AEO would not be subject to multiple inspections or verification by each AEO with which it does business;

-

Supply chain partners will be able to apply for AEO status in their own participating countries; and

-

A supply chain partner accepted as an AEO by a customs administration that participates in the Framework will be afforded program benefits by all participating administrations, including those that are phasing in implementation (ICC 2009, p. 2).

Assuming that the difficulties associated with MRAs can be overcome, the SAFE Framework provides a significant opportunity for the regulatory burden on legitimate trade to be reduced. Nevertheless, it is likely that the more recently imposed reporting requirements that have been introduced in the name of national security will remain in place regardless of the assessed status of the trader, including ISF requirements. In this context, the following question must be asked: If a trader demonstrates a commitment to global supply chain security by achieving and maintaining AEO status, does there remain a genuinely risk-based need for the trader to provide advance information to the authorities who granted that status?

The standards contained in the SAFE Framework are already resulting in a situation in which crossborder trade falls into two distinct categories – those consignments that are traded within a formally recognised secure supply chain, and those that are not. In this regard, the SAFE Framework definition of high-risk cargo is 'that for which there is inadequate information or reason to deem it as low-risk, that tactical intelligence indicates as high risk, or that a risk-scoring assessment methodology based on security-related data elements identifies as high risk (WCO 2015b, p. I/1). Indeed, recent iterations of the SAFE Framework imply that unless goods are being traded between AEOs, they are to be regarded as high risk and therefore receive a greater degree of regulatory scrutiny than goods traded within a formally recognised secure supply chain.

Conclusions

Clear trends are emerging from the evolution of the SAFE Framework and the national initiatives that have been implemented under it. More and more countries are introducing AEO programs, with a broadening scope, and mandatory advance manifest reporting is now commonplace, with its introduction in over 100 countries and its application to approximately 88 per cent of containerised sea cargo. From a trader’s perspective, having a consignment deemed low-risk at destination implies a more rapid and predictable customs clearance. At the same time, destination countries which require electronic pre-departure data are adding an additional layer of regulatory cost to trade.

There is, of course, general agreement around the international table that security is a key issue and that the principles of the SAFE Framework should be observed, including advance manifest reporting. That does not mean, however, that mitigation of the security risks expressed in the SAFE Framework genuinely reflects the national priorities of individual economies. For example, for some countries, the primary reason for implementing the CSI initiatives following 2001 had very little to do with mitigating the risk of terrorism attempts, but was more concerned with maintaining a healthy trading relationship with the US.[16]

Consequently for many economies, security-related cross-border risks may be of far less concern than more general trade-related risks. Nevertheless, whether an economy has a genuine concern about cross-border security issues, or whether they are simply paying lip service to an internationally agreed problem is somewhat irrelevant in terms of its operational impact. The tide has changed in the international trading environment, and the shift in regulatory focus to pre-export assessments and related security measures will undoubtedly continue. This is not a bad thing, provided the level and timing of regulatory intervention does not unnecessarily impede the flow of international trade. As technology evolves, such impediments will lessen. However, as is generally the case, the biggest impact will continue to be felt by exporters in less developed economies.

In comparison, USCBP is responsible for collecting 1.4 per cent of the country’s tax revenue (WCO 2015).

The SOLAS Convention is the principal international treaty relating to the security of merchant ships and ports.

This was achieved through the addition of Chapter XI-2 (Special measures to enhance maritime security) to the SOLAS Convention.

ISPS Code Part A, s 1.2.

USCBP 2016b.

USCBP 2015.

Among the most significant are the concepts of ‘Authorised Economic Operator’ and ‘Mutual Recognition’.

Based on imports for the year 2014, WTO International Trade Statistics series.

Note that scores for Category D may be inflated as they may include countries that have introduced advance manifest requirements but were not identified as such during the course of the research.

See Customs Control Act 2014 and KCS 2011.

Letter to the author from the then Secretary General of the WCO dated 13 June 2006.

See WCO 2007.

Interviews held by the author with officials from twenty customs administrations who had been tasked with implementing a range of supply chain security initiatives.