1. Introduction

In the doctrine of international customs law, research aimed at determining the contribution of international organisations to the development of international customs cooperation and national customs affairs is recognised by scholars as one of the most relevant topics. Most often, researchers focus on analysing the activities of the international organisations in this area of international relations. Establishment of such international organisations (the World Customs Organization [WCO] and the World Trade Organization [WTO]) happened after the end of the Second World War (Matsudaira, 2007; Weerth, 2017, 2020; Wolffgang & Dallimore, 2012). Less frequently, academic research mentions the contribution of the United Nations and other international organisations (Cheng, 2010; Sandrovsky, 2001).

However, in the history of international customs cooperation, long before the establishment and operation of the international organisations mentioned above, there was the founding of an international organisation that Ukrainian international scholar Sandrovsky associated with the emergence of cooperation among states in customs affairs (Sandrovsky, 2001). This international organisation was known as the International Union for the Publication of Customs Tariffs (Publication Union).

According to some other scholars, the creation of the Publication Union, as well as the International Telegraph Union, the International Union of Railways, the Universal Postal Union and other interstate associations of that time, was associated with the deepening of international economic cooperation between states and the development of the scientific and technological revolution (Amerasinghe, 2005; Barkin, 2006). Considering the lack of independent international status for such organisations in international relations and their functions, they were most commonly referred to as international organisations of a technical nature (Kuleba, 2007).

The analysis of scientific works in the field of international customs law has shown that the coverage of information on the Publication Union is extremely sparse. Mostly, researchers mention only the name, date of signing, date of entry into force and founding objectives of the convention that led to the establishment of this international organisation (Asakura, 2003). At the same time, many other important aspects of the establishment, operation and termination of the Publication Union, the first universal international customs organisation founded 61 years before the establishment of the Customs Cooperation Council, remain unaddressed.

Considering the above, this article is relevant for research on the role of international organisations in the formation and development of both international customs law and customs law of states and their associations. Therefore, the authors decided to focus on a more detailed description of the prerequisites for the Publication Union’s establishment, legal grounds for activities, legal capacity and termination.

To achieve this, the first stage of research involved analysing the centuries-old history of using customs tariffs to protect the national interests of various nations (Asakura, 2003; Mikuriya, 2018; United States Tariff Commission, 1968; Weerth, 2008). The research focuses on examples of international customs cooperation and international customs conflicts, national or treaty customs tariffs and methods of their application. In the second stage of the research, based on the provisions of the Convention for the Creation of an International Union for the Publication of Customs Tariffs (the Convention) dated 5 July 1890, the Regulations for the Execution of this Convention, and its Memorandum of Signature (the Memorandum), as well as the Protocol amending them dated 16 December 1949, the legal foundations of the activities and legal personality of the investigated international organisation were examined. In the third stage, based on the results of processing information on the expression of consent and denunciation of the Convention on 5 July 1890 and the Protocol amending it on 16 December 1949, the quantitative indicators of the members of the Publication Union at different stages of its functioning were analysed (Kingdom of Belgium, 2024). Finally, the grounds and procedures for terminating the activities of the Publication Union (including those of its states) were analysed. The results of the research were summarised and conclusions were drawn. Achievement of the research objectives necessitated the use of various scientific methods, among which the most important were historical and legal methods, dialectical methods, comparative methods, systemic and structural methods, hermeneutical methods, methods of analysis, methods of synthesis and methods of generalisation.

2. The prerequisites for the establishment and legal foundations of the International Union for the Publication of Customs Tariffs

The use of customs tariffs to regulate trade relations has a long history. For most of this history, customs tariffs were developed, amended and applied to meet the individual needs of their owners, who did not consider it necessary to coordinate their own behaviour with others. As a result, due to unpredictable, uncoordinated and sometimes deliberate actions of such participants in trade relations, the economic systems of other participants suffered significant losses. In the future, the use of similar retaliatory measures led to trade disputes and customs wars.

Conflict relations involving tariff and non-tariff trade regulation reached their peak in the late nineteenth century. Thus, between 1891 and 1896, customs wars between Switzerland and France, France and Italy, France and Spain, Spain and Germany, and Germany and Russia took place in Europe. In some cases, such as the dispute between Spain and the United States over the Cuban market in 1898, customs wars escalated into military aggression (Perepolkin et al., 2022).

As well as this, in the history of trade relations, along with conflict situations, there have been numerous examples of the development and use of customs tariffs on a contractual basis. Without focusing on the disclosure of all historical evidence of such activities, we will briefly describe the results of their implementation within the framework of classical international law. Thus, in the seventeenth century, in trade relations, the practice of determining the rates of customs duties (both national border duties and internal duties of individual provinces and cities) in the texts of bilateral trade agreements became widespread. One such interaction was the Treaty of Security and Freedom of Trade concluded in 1606 between England and France. According to its provisions, the contracting parties were obliged to ensure the limitation of certain types of internal duties and exchange information on their own customs tariffs in their relations with each other (Levin, 1962; Perepolkin et al., 2022).

In the eighteenth century, trade treaties required a structure that included a separate section on the regulation of customs and tariff procedures. In the second half of the nineteenth century, those treaties that did not contain such a tariff annex were even denied the name ‘trade treaty’. Gradually, new types of such agreements emerged: conventional or tariff agreements (Morozov, 2011).

Unlike similar agreements of the eighteenth century, the updated tariff agreements did not contain several rates of duty, but several articles under which the contracting parties mutually granted each other concessions (Kulisher, 2008).

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, the practice of applying differentiated customs tariffs became widespread in European trade relations. Its essence was that the participants of trade relations, to distinguish between preferential tariff rates for allied countries and increased rates for other countries, gradually moved from using a single autonomous tariff to a system of double tariffs – general and conventional (Morozov, 2011).

Thus, at the end of the nineteenth century, participants in international trade relations lacked not only a uniform, coordinated practice of building and applying customs tariffs, but also a practice of exchanging information on customs tariffs. The established means of bilateral cooperation on customs and tariff regulation no longer met the existing needs of the parties to such relations. At the same time, the trends of progressive development of international trade relations were intensifying not only at the regional European level, but also at the intercontinental level.

Therefore, the decision to establish a permanent multilateral international association can be considered a natural continuation of centuries of international cooperation in the field of customs and tariff regulation. To this end, 40 states and their colonies, following an international conference held in Brussels, agreed to establish an international organisation called the Publication Union by signing the Convention on 5 July 1890.

According to the website of the depositary of the Convention, on 5 July 1890, the following states became signatories to the Convention: Argentina, Austria-Hungary, Belgium, Bolivia, Canada, Chile, the Independent State of the Congo, Costa Rica, Denmark, France, Greece, Guatemala, Haiti, Iceland, India, Italy, Mexico, Netherlands, New Zealand, Nicaragua, Paraguay, Peru, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Salvador, Spain, Switzerland, Thailand (Siam), Turkey, United Kingdom, United States of America and Venezuela. This provision of the Convention also applied to Danish colonies, Spanish colonies, French colonies, Italian colonies, colonies of the Netherlands, Portuguese colonies, and the following United Kingdom colonies: Cape of Good Hope, Natal, New South Wales, Tasmania, Newfoundland, Victoria and Queensland. Subsequently, many other states that did not participate in the signing of the Convention on 5 July 1890 also became parties to the Convention. The most notable among them were Japan (2 February 1891), China (1 April 1894), Germany (1 July 1904), Sweden (6 February 1904), Poland (25 November 1920), Finland (16 August 1921) and the USSR (1 January 1936) (Kingdom of Belgium, 2024).

The structure of the signed Convention consisted of a Preamble and 15 articles. According to their provisions, the Publication Union was established for the purpose of publishing, at common expense, and communicating as soon and as accurately as possible the customs tariffs of the various states of the globe and the changes that such tariffs might undergo in the future (Bevans, 1968a).

The Convention was initially adopted for a seven-year period. Then, provided that the Convention was not denounced 12 months before the end of the first seven years, the Publication Union was to continue to function for the next seven-year term, and so on from one seven-year term to the next.

To support the activities of the Publication Union, the International Bureau, also known as the International Customs Tariffs Bureau, was established in Brussels. In fact, the International Bureau was the only body in the institutional structure of the Publication Union. The selection and appointment of the International Bureau’s staff was carried out by the Belgian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which was also responsible for providing the necessary funds and supervising the proper functioning of the established institution.

The articles of the Convention also attached great importance to many other issues; in particular, the formation of the annual budget of the International Bureau’s expenses and its maximum possible size, distribution of the joint capital in case of withdrawal from the Publication Union after the first seven-year term of operation or in case of its liquidation, accession to the Convention by other interested states and colonies and entry into force, amendment and denunciation of the Convention. These issues are exemplified in the following text from the Convention:

-

The amount of each Contracting Party’s contribution to the budget of the International Bureau was calculated by dividing the total annual expenditure by the sum of the units established for all member states of the Publication Union. The resulting number was then multiplied by the number of units assigned to each Contracting Party.

-

If any state or colony decided to cease to participate in the activities of the Publication Union before the expiration of the initial term of its operation, such Contracting Parties to the Convention would lose their right of joint ownership of the common capital.

-

In the event of the liquidation of this international organisation, the common capital was to be distributed among the member states and colonies based on the shares equitably determined in Article IX of the Convention for each Contracting Party (Bevans, 1968a).

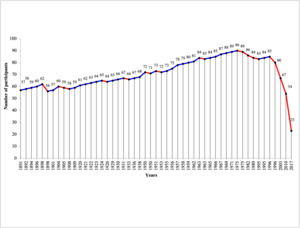

In more than a century of the Convention’s operation, 105 participants in international customs and trade relations have become its contracting parties (Kingdom of Belgium, 2024). It had its largest participation in 1975 with 90 states (see Figure 1).

The Convention had no annexes to the main text. However, according to Article XIII of the Convention, to give effect to its provisions, the contracting parties signed the Regulations. The main purpose of its signing was to detail the conditions for the establishment, financing and organisation of the International Bureau of Customs Tariffs. The Regulations consisted of a Preamble and 10 articles. In terms of legal force, its provisions were as binding as those of the Convention (Bevans, 1968c).

Along with the Convention and the Regulations, on 5 July 1890, the parties concerned also signed the Memorandum. In its contents, the contracting parties to the Convention agreed to divide all states into six classes and determined the amount of the share in the costs of the International Bureau to be paid by each state to its budget, depending on its belonging to one of the classes. The first class included England and its colonies, Belgium, France and its colonies, the Netherlands and its colonies, Russia and the United States of America. The second class included Austria-Hungary, India, Italy and its colonies and Spain and its colonies. Among the representatives of the third class were Argentina, Canada, Denmark and its colonies, Portugal and its colonies and Switzerland. The fourth class was represented by the Cape of Good Hope colony, Chile, Greece, New Zealand, Romania and others. The fifth class included Bolivia, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Haiti, Natal, Peru and others. The sixth class united Western Australia, the Dominican Republic, Honduras (Republic), the Independent State of the Congo, Newfoundland, Nicaragua, Paraguay, El Salvador and Tasmania. The contracting parties undertook to pay their financial contributions during the first quarter of each financial year, in the official currency of Belgium (Bevans, 1968b).

After the entry into force of the Convention, the Regulations and the Memorandum on 1 April 1891, the Publication Union began its own activities. For almost 60 years, the legal basis for the Publication Union activities enshrined in the above international acts remained unchanged. However, on 16 December 1949, following an international conference attended by 38 contracting parties to the Convention, it was decided that they would amend their content. This was done by adopting the Protocol Amending the Convention concerning the Creation of an International Union for the Publication of Customs Tariffs, the Regulations for the Execution of the Convention instituting an International Bureau for the Publication of Customs Tariffs, and the Memorandum of Signature, of 5 July 1890 (the Protocol).

In the Preamble to the Protocol, the representatives of the contracting parties stressed the recognition of the importance of the International Bureau’s work and noted the main reason for updating the constituent acts of the Publication Union: insufficient funds for the proper performance of the tasks assigned to the International Bureau.

For this reason, the amendments affected precisely those articles that dealt with the budgetary and financial aspects of the international organisation’s activities. Among the most significant changes were: an increase in the maximum amount of the annual expenditure budget of the International Bureau from 125,000 to 500,000 gold francs; and revision of the division of all its contracting parties from six to seven classes and the size of their shares in the costs of the International Bureau, which each such contracting party had to pay to its budget, depending on its belonging to one of the classes (see Table 1).

The increase in the number of classes also led to a change in their representative composition. The first class included United Kingdom, France, Germany and the United States of America. The second class consisted of Australia, Belgium, Canada, China, India, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Pakistan, Sweden and the USSR. Among the representatives of the third class were Argentina, Brazil, Czechoslovakia, Denmark, South Africa, Spain and Switzerland. The largest number of states were represented in the fourth class. Among them were Austria, Chile, Finland, Greece, Mexico, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Venezuela, Yugoslavia and others. The fifth class included Bolivia, Bulgaria, Hungary, Peru, Siam and Uruguay. The sixth class was composed of the Belgian Congo and Iraq. The seventh class included Albania, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Haiti, Honduras, Lebanon, Luxembourg and other states. It is also important to note that in the updated version of the Memorandum, the International Bureau was granted the right to temporarily suspend the sending of its publications to the states. This decision could have been made in case of non-payment by any contracting party of its contributions to the budget of the international organisation for more than two years, as well as considering the lack of response to reminders sent by the Government of Belgium in this regard (United Nations, 1950).

The Protocol entered into force on 5 May 1950. During the period of the Protocol’s validity, its provisions have been recognised by 72 contracting parties to the Convention (Kingdom of Belgium, 2024). The largest number of them, 70, was in 1975 (see Figure 2).

Meanwhile, some contracting parties to the Convention did not recognise the provisions of the Protocol as applicable to them for various reasons. For example, the following states had ceased to be contracting parties by the time the Protocol was in place: Guatemala (31 March 1933), New Zealand (31 March 1926), Paraguay (12 August 1950), El Salvador (31 March 1905), South Africa (31 March 1908), Honduras (27 March 1953) and Panama (16 June 1904). Russia did not recognise the provisions in accordance with the termination of its existence as a subject of international law; Serbia, Latvia, Lithuania failed to submit declarations of state succession; and Bolivia, Belgian Congo, Ecuador, China, Estonia, Albania and Uruguay remained contracting parties to the Convention without acceding to the provisions of the Protocol (Kingdom of Belgium, 2024).

3. Activities of the International Union for the Publication of Customs Tariffs

The Publication Union, represented by the International Bureau established to perform its functions, began operations on 1 April 1891. The International Bureau was obliged to report annually to the governments of the member states of the Publication Union on the results of its activities, in particular on the state of its current work and finances. Considering the significant role of the Belgian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in ensuring the functioning of the International Bureau, French was chosen as the language of official correspondence between the latter and the governments of the Publication Union member states. However, as noted by Kazansky in 1897, the member states of the Publication Union retained the right to correspond with the International Bureau in other languages, including their own national language (Kazansky, 1897).

In accordance with the purpose of the Publication Union’s establishment, as defined in Article II of the Convention, the International Bureau’s activities were carried out in two main areas:

-

publishing, at joint expense, the customs tariffs of various countries of the globe and the changes that such tariffs might undergo in the future

-

communicating, as soon and as accurately as possible, information on the customs tariffs of various countries of the world and changes that such tariffs may undergo in the future.

To ensure proper support of the Publication Union activities in these areas, the International Bureau was authorised to translate and publish – along with the customs tariffs of the contracting parties to the Convention – legislative and administrative regulations, which could be used to amend customs tariffs in the future. The received materials were published in the International Customs Bulletin (the Bulletin), using the most common commercial languages, namely English, French, German, Spanish and Italian. The government of each member state of the Publication Union was required to notify the International Bureau of the language in which it wished to receive copies of the Bulletin, which were to be sent to each state in accordance with the amount of its contribution to the expenses of the organisation. At their discretion, governments could also order copies of the Bulletin printed in different languages, if they required them (Bevans, 1968a).

Each contracting party to the Convention had the right to have all or part of the Bulletin translated and published at its own expense in any language it deemed appropriate, unless such language was one of the languages accepted by the International Bureau.

At the same time, each of the member states of the Publication Union reserved the right to reproduce simple extracts from the tariffs and, in exceptional cases, parts of the Bulletin either in its own official organ or in its parliamentary documents. In addition, each state retained the right to publish, in original or in translation, all customs tariffs, unless the text to be published was obtained because of the work of the International Bureau.

The International Bureau was authorised to take all necessary measures to ensure high-quality translation of customs laws and official publications interpreting these laws. The member states agreed that the governments concerned did not bear any responsibility for the accuracy of such translations, and that in the event of discrepancies between them, the original text would be considered the only source for action. In the event of such discrepancies, a notice to this effect would be printed in large print as a footnote on the first page of each issue of the Bulletin.

For the International Bureau to issue the Bulletin with the greatest possible accuracy, the contracting parties to the Convention undertook to send directly and without delay two copies of the following documents:

-

national customs laws and customs tariffs

-

resolutions amending national customs laws and customs tariffs

-

circulars and instructions on the application of tariffs or classification of goods, which were sent to customs authorities and could be made public

-

texts of concluded trade agreements, international conventions and domestic laws directly related to the effective customs tariffs (Bevans, 1968a).

The International Bureau translated the submitted documents with consideration to the provisions of the following well-known official documents: the Harmonised Commodity Description and Coding System of the WCO; SAC (Sistem Arancelario Centroaméricano [Central American Tariff System]); Nandina (Cartagena Agreement); Mercosur and other official nomenclatures, as well as documents determining the customs value and origin of goods.

In carrying out the translation, the International Bureau also cooperated with the member states of the Publication Union on the standardisation of their tariffs to assist them in adapting the translation of their national texts to the customs terminology of the Harmonised Commodity Description and Coding System, if their national language was not one of those listed in the Convention.

The Publication Union was the only international organisation authorised to provide official translations of customs tariffs. If any received tariff was found to be inconsistent, the state that sent the tariff was informed. Subsequently, such a state could decide to make corrections or refrain from doing so.

For a long time, the information translated by the International Bureau was disseminated through the Bulletin in printed format. Scientific and technical progress during this period led to changes in this Publication Union activity. Practically, this was reflected in the creation of its website and the use of interactive CD-ROMs to disseminate translated information. Each CD-ROM contained tariff information in all five working languages of the International Bureau. The use of CD-ROMs allowed quick searches to be made on key words or tariff codes and allowed users to print out the pages of their choice.

In general, the activities of the International Bureau significantly strengthened the work of the WCO in facilitating and promoting trade between various participants in economic relations, due to: establishing the Bulletin, including its provision in different languages; facilitating accurate and consistent translations that comply with WCO Harmonized System code usage; and adopting advancements in technology to disseminate information in a faster and more convenient fashion (Weerth, 2009, 2016).

4. Termination of the International Union for the Publication of Customs Tariffs

After analysing the history of the Publication Union, it can be stated that for almost a hundred years of its operation, there were no problems for those wishing to use the results of its activities on a paid basis. The contracting parties to the Convention repeatedly recognised the relevance of its prolongation and thus promoted the continuation of its activities for the next seven-year period.

Yet, from 1996, the number of member states of the Publication Union not only stopped increasing but also began to decrease significantly. The contracting parties to the Convention began to send notifications of denunciation to its depositary (Belgium’s Federal Public Service of Foreign Affairs, Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation) (Kingdom of Belgium, 2024).

In some of these notifications, the main reason for the denunciation was also indicated. The contracting parties considered it inexpedient to continue their paid participation in the activities of the Publication Union, since information on customs tariffs of different countries was available on the internet or in special databases free of charge. The website WorldTariff.com was mentioned as an example of one such database. In some cases, the member states of the Publication Union explicitly stated that due to the replacement of printed publications by electronic ones, the importance of the Publication Union activities had changed dramatically. At the same time, regardless of the year of denunciation, the contracting parties to the Convention continued to fulfil their financial obligations to the International Bureau until the end of the current seven-year period of the Publication Union activities (The Federal Council, 2008).

On 1 April 2010, Belgium ceased to be a contracting party to the Convention, following its denunciation on 25 March 2009. Considering the role of the Belgian Government in ensuring the activities of the International Bureau, as well as the procedure for the termination of the Convention, on 8 April 2011, Belgium’s Council of Ministers proposed to other countries participating in the Publication Union to terminate the Convention as of 30 March 2012 (SPF Chancellerie du Premier Ministre - Direction générale Communication externe, 2011).

Even though not all of the existing subjects of international customs law specified in the list of contracting parties to the Convention at that time notified the depositary of the Convention of its denunciation, 31 March 2017 became the last day of the legal existence of the Publication Union (Kingdom of Belgium, 2024). Belgium’s Council of Ministers has recognised the unpaid contributions of individual member states to the International Bureau’s expenditure budget as open debts to Belgium (SPF Chancellerie du Premier Ministre - Direction générale Communication externe, 2011).

5. Conclusion

The Publication Union was the first international organisation in the field of Customs. The purpose of its foundation was to ensure the publication, at common expense, and communication, as soon and as accurately as possible, of the customs tariffs of various countries of the world and changes that such tariffs might undergo in the future.

To directly perform the functions of the Publication Union, the International Bureau was established and operated in Brussels under the control of the Belgian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The International Bureau published the materials received from the member countries of the Publication Union in the Bulletin. The previously received materials were translated into the five most common commercial languages: English, French, German, Spanish and Italian. The materials translated by the International Bureau in the Bulletin were disseminated in print, as well as through the Publication Union’s website and as interactive CD-ROMs.

Having started its activities on 1 April 1891, the International Union for the Publication of Customs Tariffs existed for 126 years and officially ceased its activities on 31 March 2017, due to the termination of its Convention. For the late nineteenth century, having an agreement on the professional translation and publication of customs tariffs of different states into the most common commercial languages by an independent international institution was a significant achievement of international cooperation in the field of customs and tariff regulation. In the conditions of the activities carried out by the states aimed at developing a unified commodity nomenclature, the results of the Publication Union were important for collecting and summarising information on customs tariffs and customs legislation of different states. However, it can also be argued that successful attempts to develop a unified commodity nomenclature by other international organisations, including the Harmonized Commodity Description and Coding System of the WCO, and the convergence of national customs tariffs on their basis, partially influenced the relevance of the continued functions of the Publication Union. Certainly, the termination of the first international customs organisation was influenced by many other factors. The main ones could be considered to include its limited scope of activities, underdeveloped internal institutional structure, and activities made obsolete by scientific and technological progress. But the main and, in fact, the only reason for the cessation of the Publication Union activities was the lack of initiative of its member states to respond in a timely manner to changes in international customs relations and to adapt the activities of the international organisation.

Further research into the theoretical and applied aspects of determining the contribution of international organisations to the development of international customs cooperation and national Customs remains relevant. It is important for the development of the sciences of national and international customs law, as well as for the practice of law enforcement in the field of Customs in general.