1. Introduction

Customs plays a central role in combating illicit trade across borders due to its unique authority to monitor and regulate the movement of goods, people and cargos. However, in an increasingly globalised world, the demand for efficient trade facilitation has grown exponentially, often at the expense of customs control. Promoting legitimate trade while ensuring effective border security presents significant challenges for customs administrations worldwide, including a developing country like Cambodia.

In 2016, Cambodia officially joined the Passenger and Cargo Control Programme (PCCP), formerly known as the Container Control Programme (CCP) (Royal Government of Cambodia and UNODC, 2016). The PCCP, a collaborative initiative between the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), the World Customs Organization (WCO), and INTERPOL, was established through the merger of the CCP and the Airport Communication Project (AIRCOP) (WCO, 2024). This initiative is designed to enhance the capacity of law enforcement agencies, particularly customs administrations. The PCCP aims to improve customs risk management at seaports and airports by enhancing the detection of high-risk cargo and passengers to prevent illicit trade, while supporting trade facilitation objectives (UNODC and WCO, 2024).

This paper offers a critical reflection on Cambodia’s experience with implementing the PCCP. It examines both its achievements and challenges, particularly in relation to institutional capacity, data systems, staff continuity and long-term sustainability. Drawing on lessons from the field, the paper considers how Cambodia’s case can inform broader efforts to modernise customs practices and apply risk-based approaches in similar developing country contexts. In doing so, it can also contribute to ongoing conversations about the role of international assistance in supporting sustainable reform in customs administrations.

2. Overview of implementation

The PCCP continues the mission of the CCP, which aims to create a global, comprehensive approach that ensures both security and the facilitation of legitimate trade (UNODC and WCO, 2024). Currently, the program involves 87 member states, with 183 units operating within its framework (Bartoli, 2024).

In Cambodia, the program was adopted to support the Cambodian General Department of Customs and Excise (GDCE) efforts in combating illicit cross-border trade. The Royal Government of Cambodia (RGC) formally signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the United Nations (UN) for the implementation of the CCP in 2016 (UN and RGC, 2016). Subsequently, two key units were established: the Container Control Unit (CCU) in 2017 at Sihanoukville International Port, Cambodia’s main deep seaport and the Air Cargo Control Unit (ACCU) at Phnom Penh International Airport in 2018.

The program provides continuous technical and financial support to ensure the operational effectiveness of the CCU and ACCU. This includes ongoing theoretical and practical training, workshops, and mentoring on topics such as operational risk management, profiling and targeting high-risk consignments, and understanding trends in criminal activities like drug trafficking, wildlife trafficking, and the smuggling of counterfeit and environmental goods (Steilen, 2019). These initiatives enable the teams to address emerging threats within the international trade supply chain. Additionally, the program equips the units with the necessary tools and resources, such as office furniture, inspection equipment, chemical identifiers and drug testing kits.

The program also promotes networking and intelligence sharing among PCCP units through regional workshop and study tours and the use of the ContainerComm communications application, developed by the WCO. This application facilitates real-time communication and information exchange regarding illicit and high-risk consignments among participating countries. These initiatives help strengthen collaboration and develop more effective strategies for customs to combat cross-border illicit trade.

Both the CCU and ACCU are responsible for profiling and selecting high-risk shipments for physical inspection, based on risk management techniques, document and open-source analysis and intelligence sharing. These units target a wide range of illicit goods, including drugs, wildlife, counterfeit products and other prohibited items. Currently, the CCU consists of nine members, and the ACCU has 16, with staff rotating through various roles. In 2021, three members of the CCU were recognised by the UNODC and WCO as regional trainers for the program, contributing significantly to capacity building within Cambodia’s GDCE and other regional customs administrations.

Through the implementation of the PCCP, the GDCE has achieved significant successes in combating illicit trade. The CCU and ACCU have made numerous seizures, including cases of plastic and hazardous waste trafficking, illegal drugs, illicit tobacco, and other illicit goods (GDCE, 2024b). These accomplishments underscore the effectiveness of the PCCP in Cambodia in preventing cross-border smuggling and illegal activities.

3. Positive impacts

The GDCE has realised numerous benefits from the implementation of the PCCP, particularly in enhancing border security, promoting trade facilitation and driving economic development.

3.1. Strengthened customs control and enforcement

The PCCP has enhanced the GDCE’s capability to prevent illicit trade by improving customs control and enforcement capabilities. As the primary agency responsible for monitoring cross-border flows of goods, people and cargos, the GDCE plays a crucial role in detecting, deterring and combating illegal activities at Cambodia’s borders.

The enactment of Sub Decree No. 370 (RGC, 2023), which defines the list of prohibited and restricted goods, underscores the RGC’s commitment to addressing illicit trade to protect society and ensure border security. Despite the development of risk management (RM) policy through Sub Decree No. 21 (RGC, 2006), which mandates that physical inspections of consignments must be risk-based only, the challenges remain. The RM system’s limitations in effectively identifying high-risk consignments result in a high volume of physical inspections with unsatisfactory outcomes (Fellows et al., 2018). However, it is important to highlight that such inspections have provided valuable compliance data that help refine future targeting and contribute to the overall accuracy of the RM system.

The PCCP also supports the GDCE to build capability by training frontline customs officers in risk profiling and targeting techniques, equipping them with modern tools, practical skills and best practices. These enhancements streamline customs clearance processes for low-risk consignments and improve overall trade facilitation, expediting legal trade while maintaining robust border security.

3.2. Seizures of illicit trade

The PCCP has significantly bolstered the GDCE’s capacity to intercept illicit shipments, including hazardous waste, illegal drugs and wildlife products such as elephant tusks and other illicit goods. By adding an additional layer of customs control, the PCCP not only strengthens Cambodia’s border controls but also contributes to a broader framework of global border protection. This emphasises the interconnected nature of border security, where robust control at one leads to security for many.

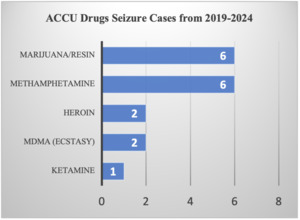

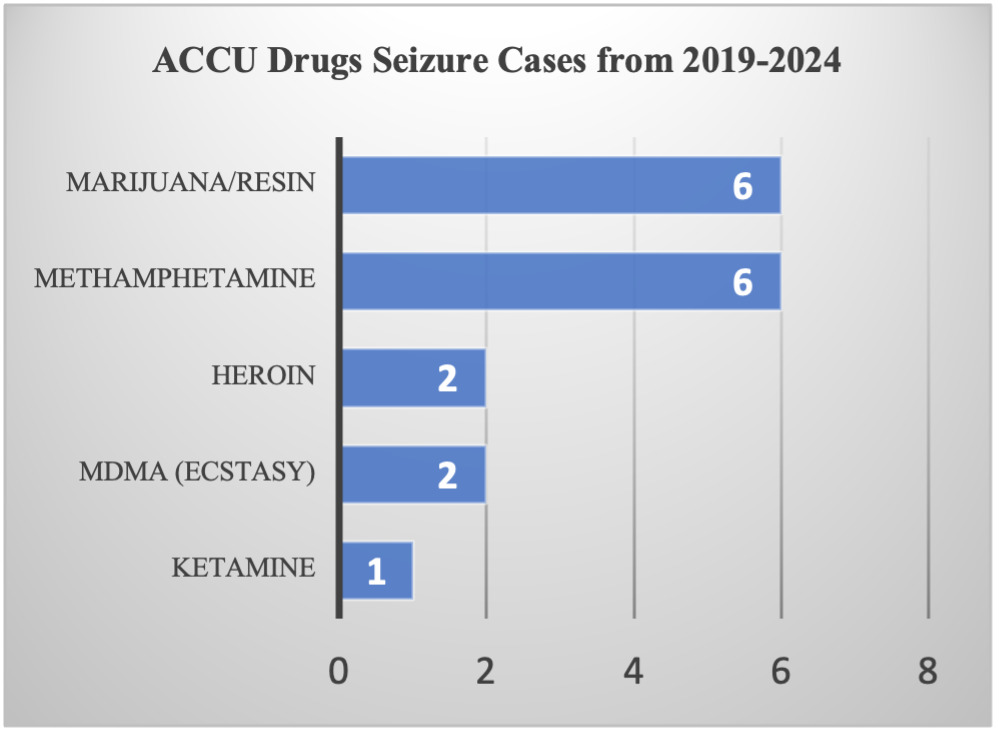

According to Figures 1 and 2, methamphetamine and marijuana/resin were the most frequently seized drugs, each accounting for six cases, with total weights of 24,415.92 g, and 17,104.16 g respectively. Ketamine ranked third in total weight at 10,000.00 g, despite being seized in only a single case. Heroin and MDMA (ecstasy) represent the smallest proportions, with each drug having two seizure cases and total weights of 1,691.70 g and 1,374.02 g, respectively.

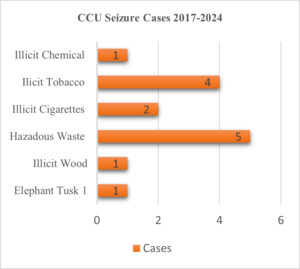

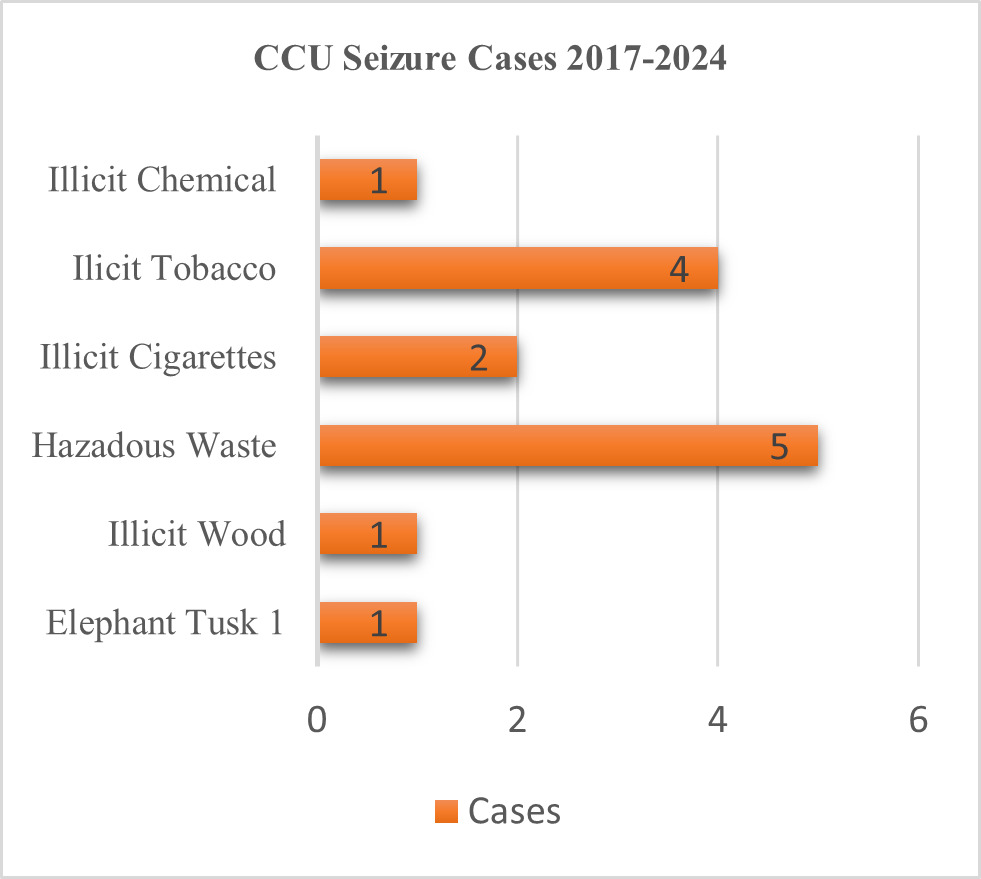

The data from Figures 3 and 4 highlight that hazardous waste was the most frequently intercepted item during this period with five cases amounting to a total weight of 1,776,532 kg. It is followed by illicit tobacco which accounted for four cases and a total weight of 75,707.50 kg. Illicit cigarettes were seized in two cases, totalling 19,235.69 kg while illicit wood, illicit chemicals and elephant tusks were less frequently intercepted, with only one case each, weighing 29,750 kg, 22,150 kg, and 941.41 kg, respectively.

3.3. Improved revenue collection

Beyond seizures of illicit trade, the PCCP has also supported the GDCE in combating revenue frauds and preventing revenue leakages. Seizures by the CCU and ACCU have sometimes uncovered cases of revenue evasion, which is critical for Cambodia as a developing country reliant on customs revenue (GDCE, 2024b). Advanced tools and risk profiling techniques provided by the PCCP enable more efficient targeting of high-risk consignments, minimising revenue leakage and supporting fiscal stability in Cambodia.

3.4. Enhanced international cooperation

The PCCP has significantly enhanced international collaboration between the GDCE and other customs administrations. Through regional workshops, study tours and exchange visits, customs officials gain opportunities to share best practices, learn from each other’s experiences, and address common challenges. These activities not only improve operational knowledge but also foster the transnational networks needed to effectively combat organised crime and illicit activities. By building these connections, the PCCP promotes partnerships and ensures a more coordinated global effort against illicit activities crossing the borders.

The WCO ContainerComm application enhances real-time information and intelligence sharing among PCCP units. It allows the secure exchange of data on high-risk shipments, enabling a unified response to illicit smuggling such as drug trafficking, wildlife, environmental items, counterfeit products and other illicit cargos. By facilitating collaboration and prioritising inspections of high-risk cargos, it strengthens global trade security and helps combat cross-border crimes effectively.

4. Challenges

Despite its success, the GDCE faces some challenges in implementing the PCCP, including technological limitations, data management issues and personnel rotation policies.

First, technological constraints hinder the GDCE from fully benefiting from the PCCP. The lack of advanced systems means that CCU and ACCU members must manually profile bills of lading and supporting documents. This process is time-consuming and less effective when it comes to identifying high-risk consignments. The absence of automated tools significantly impacts both the efficiency and accuracy of targeting, making it more difficult to effectively manage and prioritise shipments.

Second, the GDCE faces significant challenges in managing the large volumes of data generated by the PCCP due to the absence of an efficient data management system. This limitation hampers critical processes like data cleaning and integration, leading to poor data quality and inconsistent analysis. As a result, the GDCE’s ability to conduct comprehensive risk assessments and make informed decisions is significantly constrained, undermining the overall effectiveness of the PCCP’s implementation.

Third and finally, personnel rotation policies within customs administrations, including Cambodia, have impacted the sustainability of the PCCP (Steilen, 2019). For instance, some officers in the CCU and ACCU have been transferred to other checkpoints after being trained for several years, resulting in a loss of experienced personnel. The process of training new officers to replace them is time-consuming, causing disruptions in the continuity and effectiveness of the PCCP units. This ongoing cycle of turnover limits the overall performance and long-term success of the PCCP.

5. Way forwards

Following a comprehensive analysis of the status of the PCCP implementation, including its benefits and challenges, the GDCE should consider the following strategic initiatives to maximise program impact and address existing limitations.

5.1. Enhanced capacity building

The GDCE should provide ongoing training for customs officers stationed at all border checkpoints, focusing on key areas such as data analysis, risk assessment, cargo inspection techniques and emerging trends in illicit trafficking. The GDCE is well-positioned to implement this initiative, supported by three customs officers recognised as WCO expert trainers specialising in the profiling and targeting of high-risk consignments. Additionally, the GDCE has access to the WCO regional training centre in Cambodia, which could play a crucial role in facilitating and enhancing this training process.

5.2. Improved data analysis

The GDCE should develop a comprehensive and centralised data management system that can effectively process and integrate data from all data sources including the PCCP. A robust data management system will enhance the GDCE’s RM capabilities by utilising advanced technologies, such as machine learning algorithms, to automate the profiling of high-risk consignments. This will streamline operations, improve efficiency and increase the accuracy of targeting high-risk shipments, ultimately strengthening border security and trade facilitation.

5.3. Sustainable personnel development

To address personnel turnover and ensure operational continuity, the GDCE should implement strategies aimed at retaining skilled officers in the CCU and ACCU. These strategies should include establishing structured career development paths that offer professional growth opportunities within the units, as well as providing continuous training for new recruits. This will help maintain a consistent level of expertise, ensuring that the units remain effective in their mission of RM and combating illicit trade. By investing in officer retention and professional development, the GDCE can strengthen the long-term sustainability and success of the PCCP.

6. Contributions to the field of customs studies

The implementation of the PCCP in Cambodia offers a compelling case study for the customs research and practitioner community. It demonstrates how multilateral technical assistance programs can strengthen enforcement capacity and accelerate institutional modernisation in developing countries. Beyond immediate operational gains, Cambodia’s experience highlights the importance of implementing such programs within national reform agendas to ensure long-term relevance and effectiveness.

A key insight from this case is the need for institutional continuity and personnel retention. While initial training and equipment are essential, the sustainability of enforcement gains depends on the ability to retain skilled officers, integrate knowledge into daily operations, and promote leadership continuity within specialised units.

Additionally, Cambodia’s integration of PCCP methods into its broader RM system illustrates how WCO tools can be effectively localised at the frontline. This provides practical evidence on how donor-supported initiatives can serve as catalysts for transitioning from reactive enforcement to intelligence-led, risk-based control systems. However, the case also exposes challenges common to donor-driven models, particularly regarding sustainability, data integration and reliance on external expertise. These limitations prompt critical reflection on how customs administrations can balance international support with national ownership and resilience.

As such, Cambodia’s PCCP journey contributes not only operational lessons but also theoretical reflections on customs governance, program sustainability and the adaptation of global norms to local realities. It offers a relevant reference point for both customs scholars and policymakers aiming to improve enforcement strategies in similar contexts.

7. Conclusion

The implementation of the PCCP in Cambodia has brought significant improvements to the GDCE, particularly in enhancing its ability to detect and prevent cross-border illicit trade while facilitating legitimate trade. The establishment of a dedicated CCU and ACCU, combined with technical assistance and international cooperation, has helped modernise RM practices and strengthen enforcement at key border checkpoints.

To ensure these achievements are sustained, continued efforts are required to overcome persistent challenges. Investing in advanced technology, building a robust data management system, and promoting staff retention are essential steps towards improving operational efficiency and maintaining institutional knowledge within the GDCE.

Cambodia’s experience with the PCCP illustrates how targeted technical assistance can support long-term institutional development when integrated into national reform agendas. It also highlights the value of aligning global standards with local practices to support the transition towards a more intelligence-driven and risk-based customs environment. This case provides a useful reference for customs administrations and policymakers seeking to enhance border security while promoting trade facilitation in similar contexts.

_of_accu_drugs_seizure_cases_from_2019-2024.png)

_of_ccu_seizure_cases_20172024.png)

_of_accu_drugs_seizure_cases_from_2019-2024.png)

_of_ccu_seizure_cases_20172024.png)