1. Introduction

1.1. Research question and objectives

According to World Trade Organization (WTO) figures, as of the end of May 2025 there were 375 Regional Trade Agreements (RTAs) in force globally (WTO, 2025), reflecting their growing popularity and number over the years. If Rules of Origin (ROO) – one of the key elements of Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) – and other relevant provisions are applied correctly, FTAs can offer cost savings for businesses by reducing or eliminating duties on imported goods. Despite these benefits, many manufacturing businesses in sectors such as the automotive, aerospace, pharmaceutical or textile struggle to navigate the complex ROO and face various challenges (Jitsuya, 2021; Song, 2022). Moreover, origin management and compliance can be very costly (Legge & Lukaszuk, 2024), which poses additional obstacles especially for smaller companies (Small and medium-sized enterprises, SMEs). Given these complexities, exploring digital solutions and automation provides a good opportunity to ease administrative burdens and improve compliance efficiency.

To address these challenges, the following research question was formulated: what are the legal and operational constraints associated with automating preferential origin calculations in the United Kingdom (UK), with particular emphasis on the use of Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) systems, Long-Term Supplier Declarations (LTSDs), and customs software? This paper further explores how LTSDs and technologies such as ERP platforms, customs origin management software, and distributed ledger technology (DLT) can be reliably leveraged to support compliant and efficient origin automation processes. The research focuses on UK-based manufacturers of substantially transformed goods who import components or materials from third countries and face recurring challenges in managing origin documentation and fulfilling preferential origin (legal) obligations.

To guide the analysis, the following objectives were developed to provide a structured approach to understand the scope, practical applications and challenges:

-

a comprehensive exploration and assessment of existing origin management tools, including ERP and customs software

-

a review of legal and operational considerations for LTSDs utilisation

-

an examination of new and emerging technologies from the perspective of preferential origin calculation automation and traceability

-

practical recommendations for UK businesses navigating ROO requirements under FTAs focusing on the Trade and Cooperation Agreement between the European Union and the European Atomic Energy Community, of the one part, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, of the other part (TCA) (Government of the UK, 2020c).

2. Literature review

Globally, several frameworks aim to facilitate trade and provide recommendations for governments to improve country to country and government to business relationships, ensure faster border crossings, reduce trade costs and digitalise Customs. Notable examples include the WTO’s Trade Facilitation Agreement (WTO, 2017), the Revised Kyoto Convention (RKC) (WCO, 2008), and the World Customs Organization (WCO) SAFE Framework of Standards (WCO, 2021). This framework forms the foundation for trade facilitation, and guide from the broader macro-level context. Much academic research focuses on its impacts on governments and authorities, for instance, examining the trade and welfare effects of the WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement (WTO, 2023), the policies or economic impacts (Hillberry & Zhang, 2017; Hoekman, 2014; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2018), customs regulatory instruments (Rijo, 2021), legal and regulatory impacts (Czapnik, 2015; Finger, 2014; Shumba, 2024) or national regulations and country specific interpretations (UK Trade and Business Commission, 2023).

While it is important to understand trade facilitation from the macro level, focusing research at the micro level enables further exploration around the individual instruments that govern Customs and trade rules and regulations, as set out by the WCO, WTO, or the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC), such as ROO, the Harmonised System (HS), customs valuation or Incoterms®.[1] This paper explores ROO management as one of those instruments in more detail, and in the context of internationally trading businesses navigating trade and customs compliance, in conjunction with digital tools utilisation.

ROO, one of the pillars of customs compliance, are defined by Specific Annex K of the RKC as ‘the specific provisions, developed from principles established by national legislation or international agreements (‘origin criteria’), applied by a country to determine the origin of goods’ (WCO, 2008). They form an integral part of FTAs around the world, promoting international trade and foreign investments (WCO, n.d.). On the contrary, some argue about its protectionist effect, which leads to reduction of trade with non-FTA member countries (Conconi et al., 2018). Nevertheless, if understood and applied correctly, they offer reduced or zero duty rates on imported goods between beneficiary countries or parties. However, due to their complex rules and divergent contents, they can lead to misunderstandings and misinterpretations, which are often present within the textiles, iron/steel machinery and agriculture sectors (Jitsuya, 2021; Song, 2022) as well as those whose products go through ‘substantial transformation’ (European Commission, n.d.-b). The ROO legal text can be challenging to interpret by businesses, and its eligibility criteria must be met by traders wanting to take advantage of the FTA, which can also prove challenging (Hasegawa, 2021; Miles, 2018). For example, the TCA threshold for the domestic content of electric vehicles was set to increase in January 2024, which led to uncertainty and calls by European Union (EU) and UK car manufacturers to delay the increase as they were not yet ready for the required changes in content (Carey, 2023). The application of bilateral or diagonal cumulation that allows the recognition of ‘originating’ content (incorporated into a product) from another country (or countries) named in the FTA supports meeting the criteria by traders (Gasiorek & Garrett, 2020). However, the presence and maintenance of material/product content, origin and value information must be upheld to high standards, so that the adherence to FTA rules or origin can be proven to customs authorities (Government of the UK, 2020a). Additionally, leaving ‘importers knowledge[2]’ aside, depending on a specific FTA, legal evidence such as EUR1 or EUR-MED movement certificates or invoice statements/origin declarations (made out on a commercial document such as a commercial invoice) must be present at the time of declaring goods to Customs (Government of the UK, 2022). The actual origin calculation process and product eligibility for various FTA’s can be simplified and automated utilising LTSDs in combination with technological tools such as ERP systems and/or origin management/customs software. On the contrary, despite various limitations (and depending on the product’s nature or characteristics), some businesses chose to utilise excel spreadsheets (usually with Bill of Material (BOM) details), which are simple to handle and universally familiar (Higson, 2024). ERP and/or customs/origin management software, however, could calculate originating content more efficiently for more complex products, especially for highly transformed goods such as cars, aircraft, machinery, textiles or pharmaceuticals. These systems can also record and utilise supplier and raw material information while considering customer base locations for the purpose of origin calculation under various FTAs. Despite the increasing presence of digital and origin automation solutions, there is still lack of significant academic literature and legal analysis on how businesses can apply these tools in practice and/or how to align them with IT systems, operations and regulatory obligations. This research aimed to narrow this gap by methodologically analysing legal and operational constraints and providing key considerations for the practical adaption of technological solutions.

3. Methodology

The methodological approach used for this research was a combination of qualitative methods in the form of a legal review (of ROO texts of FTAs and His Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (HMRC)/UK customs guidance), expert-based analysis, case observations and a technology landscape review. To fully address the research objectives, a secondary source of available academic literature and research on ROO (and its management) and publicly available information on ERP and software provided additional exploration of key considerations and practical implications for origin calculation automation.

The study is based on a variety of sources, including FTAs, official customs guidance notes, working papers, regulatory studies, reports and academic papers published in journals. These sources were selected based on their relevance to the legal and operational constraints faced by UK-based manufacturers under FTAs and were evaluated in terms of their practical value and legal reliability.

The scope of the study was defined by its focus on UK manufacturers of highly transformed goods operating within complex supply chains, navigating preferential origin requirements under FTAs. The selected methodology provided a foundational understanding of the key challenges businesses face in managing origin compliance, including legal constraints (e.g. interpretation of ROO, definitional ambiguities, or legal documentation requirements), practical considerations (such as conducting origin calculations), and the application of technological solutions.

4. Discussion

4.1. Legal considerations, origin calculations and automation methods

In response to the research question and to support structured assessment, a set of analytical criteria was applied in addition to the general examination of legal and operational considerations/elements of FTAs and ROOs. The evaluation is based on three key dimensions: legal reliability, regulatory acceptance and cost-effectiveness. These criteria were selected to reflect the regulatory and operational realities faced by UK-based manufacturers seeking to automate preferential origin calculations under FTAs. These were applied throughout the discussion of tools such as ERP systems, excel spreadsheets, LTSDs, customs software and emerging technologies like DLT.

Many manufacturing companies utilise ERP systems to simplify business processes and improve financial efficiency (Wulan et al., 2024). Focusing on trade compliance processes, some will use these integrated systems for the storage and calculation of ‘trade intelligence elements’, such as HS (tariff) codes, ROO, or duty rates (Van de Heetkamp & Tusveld, 2011) and more. Examples of systems with such possibilities are SAP GTS and SAP S/4 HANA (SAP Community, 2023), Oracle (Oracle, n.d.), PWC (PwC & SAP, n.d.), or Visco (Visco Software, n.d.), just to name a few.

However, few ERPs can integrate or use trade intelligence data with processes enabling the actual management of origin calculations (Van de Heetkamp & Tusveld, 2011). Depending on the complexity of the manufactured product and supply chain, some businesses may rely on traditional excel spreadsheets (Higson, 2024), which can be used for BOM origin calculations. Except for requiring expert knowledge and administrative time, excel does not involve additional software costs, making it a more cost-effective option in some cases.

More technology-driven customs software solutions with origin management add-ons are among the more recognised tools for preferential origin calculations. For clarity, throughout this paper the term ‘customs software’ refers to solutions with such origin management functionality. Examples of these include PWC’s Customs origin calculation tool, AEB’s Origin & Preferences software, MIC’s Origin Calculation System–Free Trade Agreement management software, Thomson Reuters’ ONESOURCE Free Trade Agreement Management software and My Tower’s origin calculation solution. The cost of such software depends on multiple factors and pricing models, including but not limited to data volume, number of data sources, calculation complexity, ERP system integration, additional features or modules and the number of FTAs being utilised. Additional costs such as installation, licensing and maintenance should also be considered. To maximise cost-effectiveness, businesses should conduct their own cost–benefit analysis and could consider limiting origin calculations to the most complex products, focusing on FTAs relevant for their supply chains, or by opting out of unnecessary add-ons such as Optical Character Recognition modules (technology that converts image into readable text), if relevant data is already integrated via ERP systems.

Preferential origin calculations will depend on various information, such as supplier’s information (e.g. LTSDs) (European Commission, n.d.-d), determination if manufacturers’ goods are deemed as ‘sufficiently processed’ (European Commission, n.d.-b), the originating status of raw material(s) and corresponding HS codes and values, and production (including overhead/design/engineering costs), all of which will be broadly explored in this paper.

While exploring the essential ‘origin data’ needed for origin calculations, the legal considerations around definitions should be explored to provide more clarity. Although this paper is based on definitions embedded in TCA FTA (from the context of UK manufacturers), the legal definitions of ‘production’, ‘sufficiently processed’, or ‘materials’ vary among other global FTAs. For example, in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Trade in Goods Agreement (ATIGA) origin system, ‘materials’ are defined as ‘any matter or substance used or consumed in the production of goods or physically incorporated into another good or are subject to a process in the production of another good’ (WCO, 2017, p. 24), whereas in the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), ‘materials’ means ‘a good that is used in the production of another good, and includes a part or an ingredient’ (WCO, 2017, p. 24). What is meant by ‘material’ in the UK, therefore, may mean something else in other jurisdictions.

From the context of the United Kingdom’s FTA ROO, the following are some other means of proof of origin (other than LTSDs): a ‘statement on origin’ showing that the product is originating (made out on a commercial document, such as an invoice, by the exporter), EUR1/EUR-MED movement certificates, Certificate of Origin, the UK equivalent of EUR1s (the UK EUR1 Movement Certificate issued by Chambers of Commerce) and the Developing Countries Trading Scheme (formerly Generalized System of Preference) Form A. One of the main advantages of LTSDs (a specific form of supplier declaration) is that they allow suppliers to provide preferential or non-preferential origin information for multiple products within one single document. This makes supplier declarations particularly valuable for preferential origin calculations for UK businesses operating complex supply chains. A deeper examination of LTSDs therefore supports the exploration and analysis of the research question posed in this paper.

Reflecting on the macro level of legal considerations, ROO’s will differ from one FTA to another primarily due to different product-specific ROO, usually referred to as ‘List of Working or Processing Required to be Carried out on Non-originating Materials in order that/for the Product Manufactured can/to Obtain Originating Status’, often found in Annex II of most United Kingdom FTAs, or specifically in Annex 3 ‘Product-Specific Rules of Origin’ for the TCA (Government of the UK, 2020c, p. 1021). Product-specific ROOs must be evaluated and calculated in accordance with the specific criteria/rule for each free trade agreement, such as domestic content often referred to as RVC[3]/Value Added Rule/MaxNOM % (EXW) and/or Tariff Shifts, often referred to as Change of Chapter (CC), Change of Tariff Heading (CTH) and Change of Tariff Subheading (CTSH), using the particular HS chapter, heading or sub-heading (Government of the UK, 2020c, p. 1005). Additionally, the calculation methods for the value of goods also vary between FTAs, for example, the TCA uses Ex Works (EXW), whereas the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA) FTA applies Net Cost and FTAs in the US commonly use Free On Board (FOB). Nevertheless, in support of these calculations, various customs software can be utilised to calculate the originating content with country of origin (preferential and/or non-preferential) product/raw material information, provided by the supplier in the form of LTSDs. Once originating content is evidenced, most software can automatically generate an origin confirmation for the next supply chain actor/end user to support calculations for the BOM’s sub-assembly or a final product. When handling LTSDs, however, an additional layer of legal considerations arises, and certain pre-calculation checks should be carried out in advance. Among these, best practice includes verification if the wording aligns with the corresponding text set out in the relevant free trade agreement (in the TCA, the LTSDs text is stated under Annex 6-Appendix 6-B) and checking the validity period. Leaving extra administrative costs aside (such as the importer having to check the correctness of the text), non-compliance could trigger serious consequences, such as customs penalties or full import duty being applicable, which can also damage a business’ reputation. Moreover, the consequences can more deeply affect the supply chain, because missing relevant information and/or text, or an expired validity period, can negatively impact the next supply chain actor, such as the end customers, or the next tier supplier’s own origin calculation accuracy (for the end product). This ‘domino effect’ can additionally result in the final product becoming non-originating due to lack of evidence.

Automating origin calculations can be highly beneficial for both exporters and importers, including suppliers and customers, as it ensures that with verified supplier information, the end user’s or customer’s (or Tier 1, 2, and 3 suppliers) origin determination is supported by more reliable data. On the other hand, the task may be considered ineffective and/or too costly (due to administration, labour and technology investment) if the importer’s customs (or duty mitigation) strategy is other than claiming preferential origin on imports, or its own manufactured products are not complex enough and do not require sophisticated origin calculations. In such cases, businesses may decide that preferential origin calculations are not necessary, however, they should still maintain confidence about the origin of imported and manufactured goods, as this represents best practice and can support other customs compliance considerations, such as export controls/de minimis US content calculations.[4]

Other practical and legal constraints around LTSDs are ambiguities around utilisation of its electronic form as opposed to the traditional paper-based version. In the UK, official guidance on supplier declarations (Government of the UK, 2020b) states that LTSDs produced electronically do not need to be signed if the supplier’s responsible official is identified, however, according to the EU’s guide, such an (electronic) document must be electronically authenticated, or the supplier must formally accept full responsibility for any declaration made in their name without a handwritten signature (European Commission, 2018). Moreover, chapter 38 of the UK’s Electronic Trade Documents Act 2023 (ETDA, 2023) lacks coverage of paper-based alternatives for origin-management related documents like supplier declarations, as the EDTA 2023 only refers to the ‘trade in or transport of goods’ (ETDA, 2023, section 1, subsection (1)(b)(i)) (and financing such trade). On the other hand, in the UK there is an increase in the creation and submission of electronic certificates of origin, such as e-Cert or E-Z Cert, indicating a departure from paper-based processes in origin management.

Effective communication and information exchange (such as the product’s origin) with the supplier is key to building and maintaining strong supplier relationships (Aktas et al., 2022). LTSDs should be obtained by the importer/customer and updated on a regular basis – especially when the origin of the raw material origin is changed. If electronic LTSD versions[5] are deemed inadmissible by the local customs authorities (although such rejection would generally be inconsistent with prevailing regulatory practices), the importer should also request the signed original hard copies, to ensure full validity. Following compliance checks, where possible, the customer should audit its suppliers and request evidence of their origin assessment to ensure best practice. Some argue that there is an expectation that suppliers incorporate innovation into their processes so they can provide more benefits to the buyers/customers, as innovation naturally supports better information flow within the supply chain (Kim & Chai, 2017). Since customers/end users expect suppliers to conduct their own origin calculations and provide evidence, they must, at the same time, conduct their own origin determinations (so the whole supply chain is covered). The basis for origin calculations, whether managed via software, ERP or via excel, usually requires the following information:

-

part/component/material number and description

-

supplier details

-

Harmonized Tariff Schedule (HTS) code of the component/material used in the manufacturing process

-

origin and its status (preferential or non-preferential)

-

value of the component/material

-

quantity/percentage of the component/material used in the manufacturing process

-

labour/production/design/engineering costs/royalties (often referred to as overhead costs).

In addition to the analysis of the legal and practical implications, a comprehensive examination of a case study by Schüle and Kleisinger (2016), The spaghetti bowl: a case study on processing rules of origin and rules of cumulation, has been selected to drive further analysis on handling the LTSDs and BOMs in the context of preferential origin evaluations. This case study highlights the challenges faced by an automotive supplier, aligning with this research’s focus on UK manufacturers operating within complex supply chains.

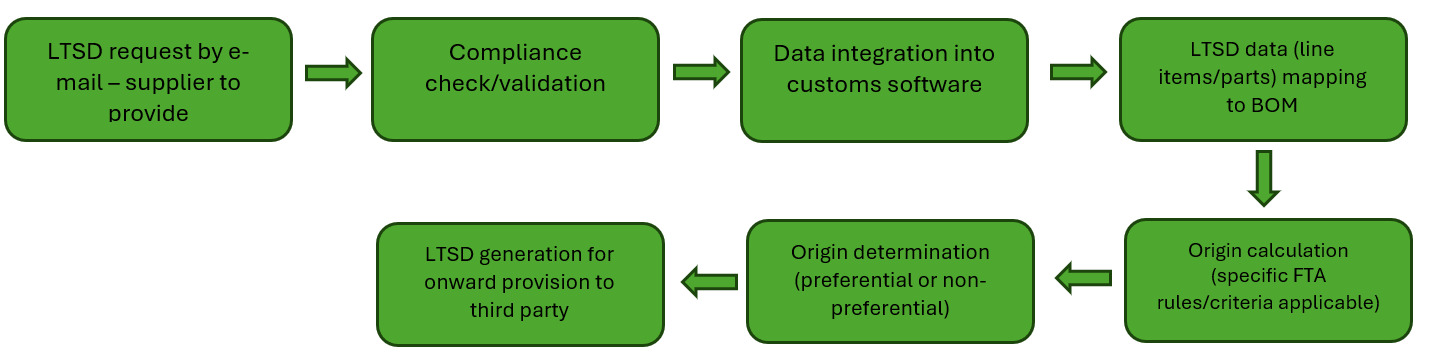

When managing preferential origin calculations via customs software, most programs will extract the necessary information from the uploaded supplier’s LTSD, with some software utilising Optical Character Recognition (OCR) for supplier declaration information extraction and submission (although not all calculation data is typically captured at this stage, as discussed further below). Information such as line item or part number and description with a corresponding HTS code and origin information, valid from/to information, and the product’s preferential or non-preferential origin status are extracted to build the BOM of a manufactured product (assembly or sub-assembly). The software then calculates the originating content for a particular FTA’s rule of origin of the product (its HS heading). Additionally, depending on the specific provisions of the FTA, the concept of cumulation[6] (treating materials from another FTA partner as originating when used in own production) may also be applied in origin calculations, provided the manufacturer opts to do so and all legal conditions are met. It is also important to ensure that the importer’s own manufacturing processes (overhead) costs are incorporated (such as labour, any product design costs or royalties), which will contribute to the final BOM’s originating content, as well as quantities of components (number of units used). Working with the software provider to ensure that all BOM details are included is crucial, especially at the implementation stage, so the logic of information sources (LTSD versus importer’s own data) is recognised, and the system can replicate and apply the same logic to other BOM’s. Considering, however, practical constraints and certain limitations, some supplier declarations may not contain the unit price of a part or a material. In such cases, the importer/customer should provide this information via other means, for example, by uploading costs in the form of an excel spreadsheet, where the part number has a corresponding unit price, or via ERP connections if possible. Exploring further automation opportunities, depending on the third party’s software capabilities, some software can additionally automate the actual process of LTSDs sourcing (for example, the MIC software). For that purpose, the program can use the supplier’s email addresses (if uploaded by the importer), and automatic e-mails containing the submission link can be sent, so importer can receive electronic versions of an LTSD.[7] Figure 1 illustrates the process of LTSD collection and BOM calculation (including verification carried out separately by the recipient).

An additional advantage of origin management automation is record keeping and simplified information access, which is especially important from the customs audit standpoint. Many origin assessment programs can be integrated into a company/client’s ERP systems (such as PWC or SAP) or can serve as an ‘add on’ to the existing customs software such as customs declarations. On the other hand, the result of the calculation is, however, dependent on the origin information of all materials incorporated in the BOM, so it is crucial the manufacturer has correct information firsthand, as calculations will only be as correct as the uploaded data. Additionally, it must be noted that some customs software can operate without LTSD input, particularly in regions where such declarations are not commonly used (United States, Asia–Pacific), for example, by relying on supplier data and embedded rule engines. Reflecting upon FTA specific considerations – and its corresponding ROO information for product calculations – some software providers may charge additional fees for conducting additional or new FTA’s or jurisdiction assessments; therefore, businesses should seek jurisdiction clarity from the beginning of the project.

Customs software is recognised as one of several digital tools used to perform preferential origin calculations. To identify alternative technological approaches to managing this task, a review of secondary academic literature and existing research was conducted. Technology that has gained increasing attention in recent years is DLT.

Blockchain, which constitutes a form of DLT, is a decentralised system for recording data and transactions (Quiniou, 2019), offering the potential to streamline digital transactions and enhance communication in international trade environments (Ioannou, 2023). This technology was successfully utilised to simplify the process of handling high volume shipping documents and tracking containers in a platform called TradeLens, a joint venture between Maersk and IBM (Jensen et al., 2019). Promotion of TradeLens within the freight forwarding industry encouraged Shipwaves (Express Computer, 2020) and CEVA Logistics (Binns, 2018) to use the same technology. While TradeLens was discontinued in 2022 due to leadership challenges and a limited deployment vision, the blockchain technology itself functioned effectively, demonstrating the potential of DLT in the shipping sector (Cecere, 2022).

Other literature, however, is more critical of DLT, with some sources questioning the veracity or accuracy of initial data entry and storage of false information (Tianyu et al., 2022). Reflecting further upon information accuracy, the same issues can be found when utilising LTSDs for preferential origin assessments.

Focusing on the topic of origin management, and according to the 2020 WCO Comparative Study on Certification of Origin, DLT could transfer sufficient and sensitive BOM information without disclosing confidential information by providing information access to certain users only. This would improve trust between third parties and could be used as a verification tool for proof of origin by providing access to unalterable information (2020) From a business perspective, considerations around access level and processes would have to be established, however, the WCO study does not specifically cover BOM calculations. While DLT offers traceability benefits, its regulatory acceptance remains limited, as few customs authorities have issued guidance or recognition frameworks for its use in origin verification. Furthermore, recognition of the legal reliability of blockchain utilisation in preferential origin management needs highlighting, because customs administrations are still at the experimental phase of the technology (WCO/WTO, 2022). Clear regulatory frameworks must be established, so that businesses can trust that the technology conforms with legal requirements and no manufacturer risks any non-compliance, and such technology is also cost-effective for businesses. Nevertheless, without clearly defined legal recognition and acceptance by customs authorities, the use of DLT in origin calculations lacks enforceable guarantees.

Another study on blockchain’s utilisation from the context of certificates of origin suggests that this solution should be assessed on case-by-case basis with its benefits carefully evaluated due to other available forms or methods of document digitalisation (Giegling, 2022). While the application of DLT for digital origin verification has been explored in the literature (Patel & Ganne, 2020), the specific application of DLT for performing the actual origin calculation remains underdeveloped. DLT has, however, been extensively explored within supply chain and international trade transactions (Davis, 2019; Yaren, 2020). Moreover, according to the 2020 WTO Blockchain and DLT in Trade study (WTO, 2020), DLT plays a key part in trade digitalisation by digitising trade documents and exchanging trade data. Further research needs to be conducted to better explore the role of DLT used specifically for origin determinations.

4.2. Other considerations – customs declarations and FTA utilisation

Further analysis comprising legal and practical perspectives in conjunction with customs software mentioned in this paper leads to considerations around automation to simplify the process of claiming preferential origin upon customs import clearance. In the scenario where a trader is self-declaring their customs declarations (e.g. via https://www.gov.uk/guidance/making-a-full-import-declaration), a certain level of additional automation can be achieved using third party customs software. In the situation where the same product is repeatedly imported to the UK under EU preferential origin, and proof of origin is obtained and valid (e.g. the invoice declaration is present on the commercial invoice along with the Registered Exporters System (REX[8])), such data could be automatically defaulted, or pre-populated, within the importer’s customs declaration software/cockpit for a specific supplier or even product (e.g. particular part reference or number). In such cases, upon import declaration creation, preference code ‘300’ could be automatically pulled together with the document and status codes U116[9] and AE (EC, n.d.-b) for origin declarations made out on the invoice. Such ‘pulled data’ would be less prone to human typing errors and could facilitate faster clearance process due to reduced manual input, which is especially beneficial when dealing with high number of goods or line items. The extent of customs declaration automation depends on the customs operations of businesses, such as their means of document and evidence presentation, for example, what proof of origin is present at the time of import as well as how and what document types are presented to customs. The more shipment patterns are recognised within importing activities, the more automation could be achieved, however, the level of automation capabilities varies from one custom software provider to another. It is important to note that under the TCA, a UK importer may claim preferential origin based on ‘importers knowledge’, however, the same legal responsibilities still apply – the importer remains responsible for ensuring the accuracy of the claim and for verifying the supplier’s origin calculations, and automation does not eliminate the need for due diligence. For that and other reasons, many customs consultancies/organisations advise businesses to use ‘importers knowledge’ with extra caution (Roche, 2023).

From an operational perspective, the utilisation of preferential origin may not always be feasible or achievable for some UK businesses (Carey, 2023). The reasons can vary from incomplete supplier information, lack of knowledge of imported goods (no product or supplier visibility), insufficient transformation of goods (e.g. painting or re-packaging, activities that are deemed ‘insufficiently processed’), not meeting the RVC content or tariff shift criteria, or lack of specialist knowledge (on ROO). Careful evaluations are necessary, and cost assessments should be conducted to establish what the real benefits would be for the business. In some instances, FTA utilisation could be too time consuming, requiring considerable administration, which some businesses with limited resources and budgets such as SMEs cannot afford (Madrid-Guijarro et al., 2009). Depending on business operations, some may find more suitable duty mitigation measures, such as Inward Processing (IP)/Outward Processing (OP) utilisation, or duty suspensions (Government of the UK, 2012). Moreover, assessment of the HTS codes of the imported products may prove that an importer is already benefiting from a very low or zero duty rates. A thorough understanding of internal manufacturing processes, HTS codes of imported products and access to import declarations data are essential for conducting such assessments. For data on imported items, a subscription to the Customs Declaration Service (CDS), which replaces the former Management Support System reports, would greatly benefit a UK importer, allowing them to check the opportunities for duty mitigation measures. Furthermore, various tools such as Microsoft’s Power BI or Salesforce’s Tableau can be utilised to support data visualisation of the CDS report (Skender & Manevska, 2022).

5. Conclusion

In the complex realm of ROO, the automation of origin assessments for sufficiently transformed goods offers substantial benefits, especially from a customs compliance standpoint. It enables more efficient and accurate determination of product eligibility for preferential treatment under FTAs, facilitates record keeping and information access, and supports rapid recalculations in case of any changes in supplier or product information. Automation can also strengthen the trust and collaboration across supply chains by ensuring a consistent and traceable approach to origin data management. These findings suggest that technological tools, when applied correctly, not only improve trade compliance, but also facilitate more efficient customs operations and improve cross-border supply chain integration.

5.1. Policy implications

Deciding to automate preferential origin should be based on careful assessment of legal requirements, cost efficiency, business needs and operations, however, automation offers a practical way for businesses to enhance data visibility and strengthen trade compliance management. It must be approached with careful consideration of legal frameworks, supplier coordination and data quality requirements.

From a legal and policy standpoint, this research highlights a growing need for clearer regulatory guidance around the recognition of digital tools utilised for preferential origin management such as LTSDs and DLT, particularly in the UK-EU context. Additionally, regulatory harmonisation would facilitate legal certainty as well as cross-border interoperability.

5.2. Future research

This study focused on ‘substantially transformed’ goods rather than the ‘wholly obtained’ concept, which is still relevant under FTAs. It did not examine non-preferential ROO (and their role in global trade for statistical valuation purposes, anti-dumping/countervailing/sanctions measures or origin labelling), and other FTA provisions such as de minimis, accessories provisions, or treatment of packaging. Future studies could expand this research by examining these areas in more detail and how automation and digital tools could interact with non-preferential rules or special provisions within FTAs.

Moreover, this paper identifies academic literature limitations around the DLT technology utilised for preferential ROO calculations, therefore further research on this topic is recommended. Legal recognition of DLT in origin management also remains limited, as customs authorities have yet to establish enforceable frameworks. Furthermore, regulatory harmonisation should be pursued to ensure that rules governing electronic LTSDs are consistent across both the UK and the EU. Any future innovations should be aligned with evolving regulatory expectations on both sides. This regulatory alignment is key to ensure the legitimacy, scalability and legal enforceability of automated origin management processes.

5.3. Final remarks

This study provides a valid foundation for manufacturers looking to strengthen their trade compliance and digital processes in origin management. By offering practical insights and legal considerations, it supports businesses in making informed and technology-driven decisions that promote innovation and facilitate trade. In doing so, the paper also draws attention to a broader gap in academic literature, namely how legal obligations under the FTAs can be operationalised through origin automation tools, highlighting the need for further investigation into practical applications and regulatory alignment.

These are a set of standards issued by the ICC ‘used in international and domestic contracts for the delivery of goods…[they] help to avoid costly misunderstandings by clarifying the tasks, costs and risks involved in the delivery of goods from sellers to buyers’ (ICC, n.d.).

Importers knowledge – the provision under the TCA allowing UK/EU importers to claim preferential origin based on the knowledge that goods are preferential.

Regional Value Content.

In the US Export Administration Regulations (EAR) the de minimis rule applies to foreign-made products containing specific percentages of controlled US-origin materials.

Given the differences between the UK and the EU guidance on supplier declarations, or if in doubt, businesses could choose to check with local customs authorities if electronic LTSDs can serve as valid evidence, for extra reassurance.

It must be noted that there are various types of cumulation such as Bilateral, Diagonal or Full (EC, n.d.-a).

Given the differences between the UK and the EU guidance on supplier declarations, or if in doubt, businesses could choose to check with local customs authorities if electronic LTSDs can serve as valid evidence, for extra reassurance.

REX – EU authorisation that can be obtained from customs authorities, enabling EU exporters to provide certification of origin (e.g. using an origin statement on commercial invoices with REX number); used when exporting consignment values of €6000 EUR or over (REX status eliminates monetary value limit) (EC, n.d.-c).

U116 is a ‘Statement on Origin’ for EU-UK TCA, usually made out on a commercial invoice, for status codes AE, AF, AG, AP, AS, AT, GE, GP, JE, JP, LE, LP, UA, UE, UP or US. U118 could also be considered for the ‘Statement on Origin for multiple shipments of identical products.’