1. Introduction

On 1 July 2021, new value-added tax (VAT) rules on the import of goods worth less than EUR150 were introduced in the member states of the European Union (EU). According to the European Commission (EC), these rules are part of the efforts to ensure a more level playing field for all businesses, to simplify cross-border e-commerce and to bring more transparency to EU buyers in terms of pricing and consumer choice (EC, 2021). The EU’s VAT system was last updated in 1993 and is no longer in line with the growth of cross-border e-commerce, which has significantly transformed retailing in recent years. The new rules also respond to the need to simplify administrative formalities for imports both for sellers and buyers, and for postal operators and couriers. At the same time, they also directly affect the activities of the customs and tax administrations in the EU member states. However, the procedural simplifications provided for economic operators are accompanied by several risks, which directly impact the fiscal and protective functions of Customs.

The aim of this article is to characterise the features of the new EU VAT rules on cross-border e-commerce and outline some of the main challenges facing Customs in this area. Firstly, the main features of the new EU VAT rules on cross-border e-commerce are outlined. Then, the VAT procedures currently in force on importing consignments not exceeding EUR150 are reviewed. Some of the main challenges facing Customs when levying VAT on cross-border e-commerce are also highlighted. Finally, the trends in processing low-value consignments under the new VAT rules in the Republic of Bulgaria are tracked.

2. The problem

In online retailing, consumers can purchase the goods they need directly from manufacturers without using the services of intermediaries or other merchants. Today, it is quite possible to buy any good online without having physical contact with the seller, and the price is often competitive with that of wholesaling. Cross-border e-commerce provides a new mode of business transactions and exerts a fundamental influence on the way in which commercial trade is conducted (Wang, 2017). In turn, this entails several risks, both in terms of the type and quality of the goods sold, and in terms of their real value. These risks are, in principle, the main object of customs control, and in e-commerce managing them is a real challenge for the regulatory authorities. Therefore, in recent years, cross-border e-commerce has occupied an increasingly tangible place among the legal regulation of customs activity, and mechanisms are constantly being sought to guarantee the interests of both society and the fiscal systems of the individual countries.

In its policies, the World Customs Organization (WCO) pays special attention to e-commerce, thus recognising its importance to the systems of customs control on a global scale. In June 2018, the WCO accepted the Cross-Border E-Commerce Framework of Standards (the Framework), which articulates a set of fundamental standards along the key principles identified and adopted in the WCO Luxor Resolution on Cross-Border E-Commerce (WCO, 2022). The Framework provides the standards for the effective management of cross-border e-commerce from both facilitation and control perspectives. Of special interest to this article is Standard 8: Models of Revenue Collection, according to which:

Customs administrations, working with appropriate agencies or Ministries, should consider applying, as appropriate, various types of models of revenue collection (e.g., vendor, intermediary, buyer or consumer, etc.) for duties and/or taxes. In order to ensure the revenue collection, Customs administrations should offer electronic payment options, provide relevant information online, allow for flexible payment types and ensure fairness and transparency in its processes. (WCO, 2022, p. 12)

Along with the USA and China, the European region is among the largest contributors to international retail turnover generated through e-commerce. In the EU member states in 2021 about 20 per cent (over EUR718 billion) of retail sales were realised online, and here, too, there has been an upward trend in recent years (Eurostat, 2022). Over 22 per cent of this turnover (about EUR158 billion) was realised from purchases of goods from third countries, which are subject to the customs control systems of the member states (Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences & Ecommerce Europe, 2022, p. 14). The analysis of the role and importance of Customs in relation to these goods cannot be made solely based on their value, since besides collecting customs duties and other taxes, Customs has several other functions and tasks. Online trade usually involves the movement of small consignments of relatively low value, but it should always be remembered that there is a risk that they pose a threat to the economic or vital interests of their consumers in the EU.

The rise of e-commerce has led to significant changes in the consumer behaviour of millions of people around the world. An additional push in this direction was given by the COVID-19 pandemic, which, until recently, changed the course of socioeconomic life as we knew it. The possibilities of purchasing goods from a distance have unfortunately also proved to be a good environment for the development of several illegal practices affecting both the persons involved in commercial transactions (sellers and buyers) and the competent state authorities exerting control over them. Controlling this particular flow of goods to prevent the movement of prohibited and restricted goods and identify consignments that have been split and/or undervalued to evade duties and taxes presents a number of challenges. They include the collection of electronic advance information on e-commerce consignments, the improvement of compliance and data quality, the simplification of duty and tax payment procedures, which are often too complex, and the strengthening of risk analysis capacities (Mikuriya, 2021). The regime for not levying customs duties and VAT on the import of the so-called ‘low-value consignments’,[1] existing for many years in the EU, allowed unscrupulous traders and importers to take advantage of such opportunities and import goods illegally into the EU. It is very difficult to prove such fraud by using the current means and methods of customs control, relying primarily on risk analysis and physical checks of part of the consignments. Considering, however, that more than 150 million small consignments enter the territory of the EU member states annually, it is in practice impossible for the customs administrations to check them all effectively. Thus, some of these goods are released for free circulation, although they are a potential object of fraud. According to data from the EC, this omission costs the EU budget about EUR7 billion per year in the form of unpaid duties and import VAT, which leads to a greater tax burden for regular taxpayers (EC, 2017).

The EC constantly considers the challenges of cross-border e-commerce as listed above and seeks legislative measures to ensure the correct and uniform manifestation of the fiscal and protective functions of Customs in all EU member states. The actions taken to implement the advance cargo information system — Import Control System 2 (ICS2) — are a good example of regulations aimed at limiting illegal trade and increasing the levels of security and safety in terms of the goods imported into the EU. This system will not only help limit fraud, but it also aims to achieve faster processing of consignments and complete digitisation of their import process. An important feature of ICS2 is that the first releases of its implementation cover postal operators and air express couriers (EC, 2019). The new VAT e-commerce package, which introduced several changes in VAT and customs legislation, aimed at responding to the variety of challenges raised by e-commerce, has also had a significant effect in this respect. From 1 July 2021, several amendments to Directive 2006/112/EC (the VAT Directive) came into effect, affecting the VAT rules applicable to cross-border business-to-consumer (B2C) e-commerce activities. The European Council adopted these rules by Directive 2017/2455 in December 2017 and Directive 2019/1995 in November 2019 (VAT e-commerce Directives). The purpose of the package was to level the playing field for businesses, reduce the complexity of the provisions, decrease the compliance burden and provide for more fraud-resistant rules. While it could be concluded that several of the new provisions will indeed contribute to achieving these objectives, others seem to go against them (Papis-Almansa, 2019).

Of interest in this area is the possibility of taking measures in the EU in the future to remove the threshold of EUR150 for charging duties. A similar recommendation is contained in the Report by the Wise Persons Group, which also proposes to provide some simplification for the application of customs rates for low-value consignments (Directorate-General for Taxation and Customs Union, 2022, p. 33). Here, the discussion is yet to come, as it is currently unclear to what extent such a move is justified in terms of additional administrative costs for customs administrations. Currently, only 25 per cent of the total amount of duties collected[2] remains in the member states, and considering that these are low-value consignments, it may turn out that the costs of processing them exceed the potential revenue. In this regard, so-called tax analysis, dealing with the question of what effects the changes in tax policy (especially tax rates and tax bases) will have on government revenues, is essential (Haughton, 2008).

On the one hand, these measures by the EC regarding the cross-border taxation of e-commerce aim to limit the shortage of customs revenues and the possibilities of avoiding paying them. On the other hand, however, these measures lead to the simplification of customs formalities for a certain category of goods. According to Grainger (2008), for most practitioners, trade facilitation revolves around ‘better regulation’, and utilising information and communication technology.

3. Features of the new EU VAT rules on cross-border e-commerce

The new VAT rules on cross-border e-commerce of low-value consignments were introduced in the EU on 1 July 2021 as an attempt to overcome the problem of VAT evasion. In addition to the effect on the collection of this tax, the new changes also aim to ensure that the tax will be paid in the member state in which the goods will actually be consumed. With changes in the national tax legislation of the EU member states, two VAT thresholds of postal and courier consignments from third countries, which are the subject of distance sales and are addressed to a natural person in the Union, have been differentiated. In the Republic of Bulgaria, these changes are regulated in Article 57a–57e of the Value Added Tax Law (Bulgarian State Gazette, 2006):

-

Consignments of intrinsic value worth up to EUR150: are subject to VAT according to the rates for the goods contained in them, applicable in the EU member state in which these goods are actually declared and imported. These consignments continue to be duty-free under the provisions of Articles 23-24 of Regulation (EC) No. 1186/2009 (European Union, 2009). They are allowed to enter the territory of the European Union under this condition after submitting a customs declaration electronically (Single Administrative Document – SAD) of a super-reduced dataset (H7)[3] of Annex B of the Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) No. 2015/2446 (European Union, 2015), as long as the goods are not subject to prohibitions and restrictions and are not excise goods.

-

Consignments of intrinsic value exceeding EUR150: these consignments are subject to customs duties and VAT (according to the VAT rates applicable in the country of import), and for the purposes of their customs clearance, a standard customs declaration is submitted electronically under column H1 of Annex B of the Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) No. 2015/2446.

The new regulatory regime regarding the importation of low-value consignments means that in such cases, from a fiscal point of view, the customs declaration of super-reduced dataset (H7) must be submitted not so much for customs purposes as for VAT purposes. Some authors even raise the question to what extent such declarations should be called ‘customs’, since they do not fully cover the objectives of customs control (Bowering, 2018). In practice, the customs authorities take on the role of revenue authorities and assume all responsibility for the VAT administration on such imports without the option of subsequent control by the tax authorities, since in most cases importers are non-taxable persons under the VAT legislation. The goals of the economic policy of each country are reduced to providing financial resources for the country, creating conditions for regulating the economy, as well as influencing the emerging inequality in market relations and income levels of the population (Zhelev, 2020). At the same time, however, Customs has significantly wider powers and responsibilities, such as control over the type and purpose of imported and exported goods.

4. Procedures for levying import VAT on consignments of goods worth up to EUR150

The new VAT regime has led to the need to develop and implement new customs procedures to ensure that imported goods circulate freely in the EU, including the updating of the customs import information systems operating in the member states. To implement the changes above in the VAT regime from 1 July 2021, an updated version of the Customs Import Information System (CIIS) of the Customs Agency was put into operation in the Republic of Bulgaria. It ensures the electronic submission of the new import declaration of a super-reduced dataset (H7), which can be submitted personally by the recipient of the consignment or by a customs representative authorised by the recipient (such as a courier or postal operator). Regardless of who appears as a declarant of the goods before the customs authorities, they need to have a qualified electronic signature (QES), a valid Economic Operators Registration and Identification (EORI) number[4] and registration for electronic data submission in the E-Portal of the Customs Agency.

Currently, in European customs practice, there are three customs procedure options, within which the consignments of goods having an intrinsic value of up to EUR150 are processed.

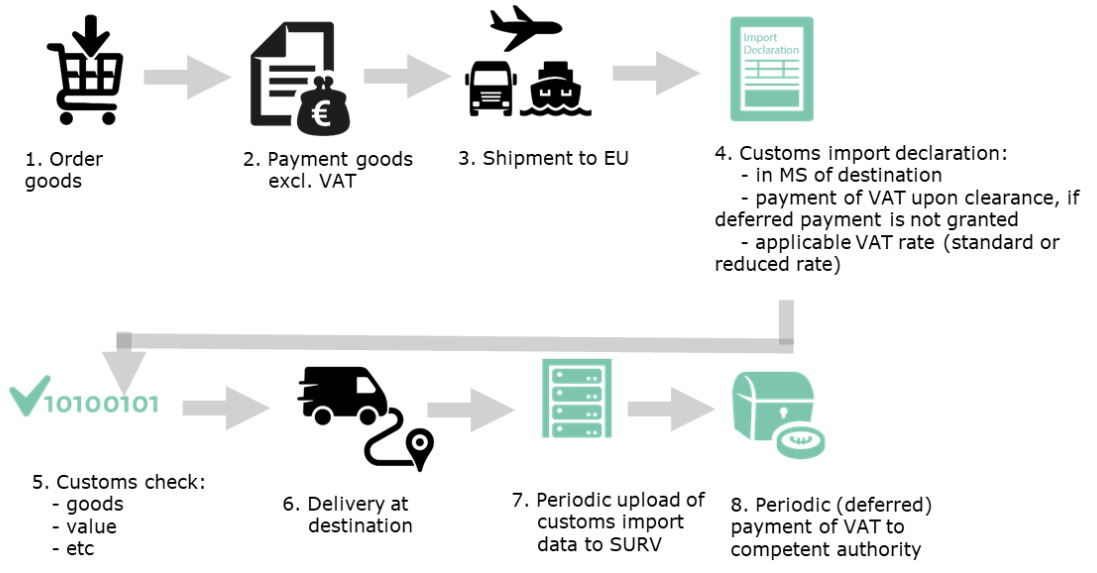

4.1. Standard procedure

This partially preserves the philosophy of the old regime of customs clearance of such consignments, the difference being expressed only in the absence of de minimis when levying import VAT (Figure 1). Once an order has been placed with a third country seller by an EU buyer and the latter has paid the value of the goods and possibly the transport and insurance costs, they are physically transported to the member state where the buyer is located. Upon the arrival of the goods and after they are presented to the customs authorities, the recipient, or a person authorised electronically by the recipient (customs representative), submits an import declaration of a super-reduced dataset (H7) and pays the VAT to the respective customs office. Customs authorities can carry out documentary and physical checks on the goods, their value and tariff classification being of particular interest. The first check is aimed at preventing the declaration of undervalued goods and the unlawful avoidance of paying customs duties and VAT, while the second is aimed at establishing the existence of a risk profile for these goods and their falling into a certain import permit or registration regime. If the VAT due has been paid and no inconsistencies have been found during the checks carried out by Customs, then the goods can be released and delivered to their recipient. Customs authorities must regularly send all relevant data from customs declarations to the EU VAT Surveillance system to produce the monthly reports that the VAT legislation requires.

The two new options for collecting VAT when importing consignments with an intrinsic value not exceeding EUR150 contain elements that simplify customs formalities, which is a requirement for their higher efficiency.

4.2. Special arrangement with deferred import VAT payment

This procedure (Figure 2) is regulated in Title XII, Chapter 7 of the VAT Directive (European Union, 2006), and specifically for the Republic of Bulgaria in Article 57a–57e of the VAT Law. A specific fact about this procedure is that after the goods have been ordered, the payment is made to the seller in the third country (including the possible transport and insurance costs, if they are at the buyer’s expense), and transported to the buyer’s member state, an import declaration of a super-reduced dataset (H7) is electronically submitted to the customs authorities, but the VAT due is not paid at the time of importation. In practice, the payment of VAT is postponed, and the declarant must be a person acting as an indirect customs representative of the recipient (such as a courier or postal operator). This person must also be the holder of a deferred payment permit and provide the customs authorities with a bank guarantee assuring the future tax payment into the state budget. Upon acceptance of the H7 declaration by the customs authorities, like the standard procedure above, they can carry out documentary and physical checks of the goods if there is a justified need for this. If there are no discrepancies, the goods are released for free circulation in the EU and are delivered to the recipient, who at the time of their acceptance must pay the courier the import VAT. In turn, the courier or postal operator is obliged to keep an electronic register for the purposes of the special arrangement, which allows the customs authorities to verify its correct application. The tax collected from the recipients for the relevant period must be paid into the account of the relevant customs office that processed the import no later than the 16th of the month following the month of import, and for this purpose a monthly declaration must be submitted electronically.

The special arrangement with deferred payment of the import tax brings benefits to all participants in this process – the recipients of the goods, the couriers and the customs authorities. The recipients of the goods do not need to interact directly with Customs and know in detail the customs regulations applicable to the goods they purchase, and they must pay the import VAT due only if they accept the consignment. Couriers do not need to complete standard customs declarations and wait for the possible advance payment of VAT by the recipients, which results in faster customs clearance of goods and freeing up of their warehouses. Regarding the customs authorities, the achievement of 100 per cent VAT collection can be considered as an important benefit of this arrangement, since in practice the payment is a commitment of the indirect representative and not of the individual recipients of the goods.

4.3. Import One-Stop-Shop (IOSS)

The IOSS (Figure 3) is a special procedure for distance sales of goods imported from third countries or territories set out in Title XII, Chapter 6, Section 4 of the VAT Directive. Under it, the suppliers of low-value consignments must register in advance with a member state tax office of their choice, and those who are based outside the EU must indicate their accredited representative with headquarters in the EU. The tax office issues individual IOSS identification numbers to suppliers for their registration under this regime. When a non-taxable person established in the EU orders goods through an electronic interface of a third country IOSS operator, along with the price of the goods, they also pay the VAT due according to the applicable rates in their member country. This means that under this procedure the import VAT is administered by the foreign IOSS operator, and the responsibility for its correct determination and collection is theirs. Once the goods are delivered to the EU, they are declared electronically to the customs authorities using a super-reduced dataset import declaration (H7). The consignment is subject to automated Customs and if there is not a risk profile in relation to the type and nature of the goods (based on the tariff number), their declared intrinsic value is below EUR150 and the indicated IOSS number is valid, then the goods are considered released for free circulation. In practice, the goods are delivered to the final recipient without the need for them to have any relationship with the customs authorities and without the tax on their import being effectively paid into the state budget at that moment. Each month, the supplier or their accredited representative submits an electronic VAT return (report) to the tax office of their choice and pays into its accounts the tax collected from all transactions carried out under the IOSS procedure, regardless of the EU member state in which the recipients of the goods are located. It is the duty of the relevant tax office under the IOSS operator registration to forward the collected import VAT to the tax offices of the EU countries where the buyers of the goods are located.

The IOSS regime provides several procedural simplifications regarding the declaration and payment of import VAT, which affect all parties involved in these transactions – non-EU online sellers, EU buyers, and customs and tax authorities of the member states. Some positive effects of this procedure are that:

-

sellers charge and collect the import VAT due at the place of sale in the third country. This is more efficient than the former practice in the EU of collecting VAT on imports at a later stage when the goods are already physically imported into the EU, as their recipient may refuse them, or neither pay VAT nor return them to the sender.

-

the buyer is aware in advance of the amount of VAT on the purchase due in their country and pays it to the seller. They can be sure that they will not face additional payments when the goods are delivered to the EU.

-

sellers need to register and remit the VAT collected on sales to EU customers in only one member state, although they can sell goods to buyers located throughout the EU. The collected VAT from all sales to recipients from all EU member states is paid to the tax authorities in the country of registration monthly, until then IOSS operators can operate freely with these funds.

-

there is more efficient customs clearance as IOSS enables consolidated presentation of consignments to one customs authority to be released for free circulation throughout the EU. In practice, the IOSS scheme is an exception to the rule that the competent customs office before which the goods are declared for import is the customs office located in the EU member state where the transport and delivery of the goods ends.

5. Challenges to Customs in levying VAT on cross-border e-commerce

The new EU VAT rules on cross-border e-commerce of low-value consignments bring several advantages and simplifications for both economic operators (such as sellers, buyers, couriers and postal operators) and customs authorities. At the same time, these new rules will likely produce some new challenges for the customs authorities regarding low-value consignments, which need an adequate response. The customs administrations of the EU member states are obliged by law to exercise control over cross-border commerce and fulfil their fiscal and protective functions, to defend the interests of European consumers and generate revenue for both the EU and its member states (in the form of the so-called Traditional Own Resources, or TOR). Exercising effective Customs on the range of goods in question is, on the one hand, very difficult due to the large number of small consignments that are delivered daily to recipients in the EU. In practice, customs authorities have limited resources (staff and technical means of control), which does not allow them to physically check all goods crossing the external borders of the EU. Therefore, Customs must select the consignments subject to control and check only those in which the levels of fraud risk are high. On the other hand, Customs is placed in a situation where it must increasingly trust the economic operators engaged in this commerce, and especially those who are holders of the special VAT regimes for the importation of low-value consignments mentioned above. This transfer of risk from Customs to businesses implies that the preliminary control regarding the persons applying for access to these regimes is duly implemented and that the criteria and conditions required for this are fulfilled. In other words, Customs must be absolutely convinced that all requirements are met, because in practice part of its fiscal function is transferred to businesses and it does not fully manage the risk of fraud. In this sense, the preliminary checks of the persons who will have access to these procedures are very important.

Considering the nature of this type of commerce and the specifics of the new import VAT regimes for consignments worth less than EUR150, there are some challenges facing Customs, such as:

-

undervaluing the declared intrinsic value of the imported goods so that it falls below the threshold of EUR150 and avoidance of the payment of customs duties. Such action should be treated as customs fraud, which is regulated in Art. 234 of the Bulgarian Customs Law (Bulgarian State Gazette, 1998). Such frauds are difficult to detect and prove, in view of the fact that in trading with such small consignments, commercial documents are not always available or their credibility is questionable.

-

incorrect tariff classification of goods and avoiding the implementation of non-tariff measures introduced in relation to them (prohibitions or restrictions) on imports. Such action should also be treated as customs fraud according to Art. 234 of the Customs Law. The circumvention of EU trade policy measures can lead, for example, to the unregulated import of goods dangerous to the life and health of the population, which would not be released for free consumption without the presentation of the required documents (such as certificates, licences, opinions and permits). The only effective way to detect such fraud is to carry out a physical examination of the dutiable consignments and compare their contents with what has been declared. As the number of low-value shipments is very high, it is in practice impossible to do this for all consignments. It is precisely the risk of such frauds that prevents the use of the so-called generic tariff number for low-value consignments.

-

Smuggling compromises the fiscal elements of customs control as well as the protective elements. As stated above, full physical control over low-value shipments and comparison of the data in the customs declaration with their actual contents is impossible. The risk of an incomplete declaration, and the avoidance of applicable tariff and non-tariff measures, is high if there is not full control of the shipment. Such an act is treated as a customs violation according to Art. 233 of the Customs Law and, if found, is subject to serious penalties.

-

infringing intellectual property rights, which is one of the most common violations when importing goods by means of courier or postal consignments because often the senders are in the informal or grey sector of the economy. The question here is to what extent is it possible to determine whether the goods are genuine or counterfeit, as a trade name is not indicated in the H7 declarations. This, in turn, does not allow the direct operation of the established customs mechanisms to counteract such imports, and the detection of counterfeit goods is possible only through carrying out physical examination by the customs authorities, who have received thorough training in the identification of such goods. On the one hand, the problem is grave, as it can involve cosmetics, medicines, electronic devices, children’s toys or other goods that are used directly by people and can have a direct impact on their life and health. On the other hand, the quantities are small and the national supervisory authorities on the market may identify such goods if they are put up for sale in the Union.

-

submission of invalid or wrong IOSS numbers by a fraudulent third country supplier when an EU buyer orders the goods. Such fraud or error is a prerequisite for wrongful collection of VAT, which will subsequently not be remitted to the tax authorities in the EU and, upon importation, the buyer will have to pay it again. Such a situation is a serious risk area for this new import VAT regime on low-value consignments. Due to the presence of such a problem, some couriers in the EU are worried about transporting consignments with IOSS numbers, since (at least now), there is no mechanism for checking their validity by the economic operators. If during import the customs authorities find an invalid IOSS number, the recipients of the goods can refuse to receive them and refuse to pay VAT again. This causes the overloading of the couriers’ warehouses with abandoned goods, paying additional costs for their storage, returning them to the sender or destroying them

-

fraud committed by importers for paying less or more VAT through the IOSS system.[5] This involves specifying the place of delivery and imposing customs duty on the ordered goods in a member state with lower rates of VAT, but delivering to another member state. IOSS solves several problems from a customs point of view, but since it involves non-taxable persons under the VAT legislation, it cannot be established where the actual consumption of the goods imported under this procedure will be to charge the applicable tax rate in that location

-

refusal by the recipient in the EU to accept the consignment, which leads to several problems for couriers and postal services. On the one hand, these problems are purely financial, related to the additional costs of returning the consignment to the sender, its storage or destruction. On the other hand, it should be considered that consignments containing goods posing a danger to the life and health of people or the environment, for which Customs has demanded to obtain the relevant import permits, are usually not released. These consignments remain in the warehouses of couriers or postal services, which may not have the necessary conditions for storing them and thus endanger the remaining stock or even the integrity of the warehouse, as well as the life and health of the warehouse workers and control authorities.

These challenges are present to varying degrees for individual EU member states and their customs systems, such as those for standard customs clearance of commercial shipments. There is a systematic absence of common implementation of customs measures, different control practices across border entry points, both within and across member states, differences in control priorities, and differences in methods and sanctions for non-compliance (Directorate-General for Taxation and Customs Union, 2022).

6. The case of Bulgaria

E-commerce in Bulgaria follows the global trends of constant growth, but the number of shipments and the total value of the goods in the transactions are still below the average levels for the EU as a whole. According to data from the Bulgarian E-commerce Association (BEA), the total turnover of B2C online commerce for 2021 was up 29 per cent compared to 2020 and reached EUR1.2 billion (BEA, 2022). The European e-commerce report for 2021 shows that in Bulgaria about 17 per cent of online purchases of goods (about EUR200 million) are from third countries. The average EU level of this indicator is 22 per cent (Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences & Ecommerce Europe, 2022).

In terms of the present study, the volumes of trade and the VAT on the so-called low-value consignments with an intrinsic value of less than EUR150 are of interest. The data for these are provided by the Bulgarian customs administration (Table 1). The data show that for the period 1 July 2021 to 30 June 2022, a total of 280,658 customs declarations (SAD) of a super-reduced dataset (H7) with a declared customs value of over EUR12.3 million were submitted and processed. Compared to the total volume of online commerce with third countries, it is obvious that only about six per cent of it is classified as low-value consignments. The summarised data show that the average declared value of one declaration is EUR43.95, which at an applicable VAT rate for import into Bulgaria of 20 per cent gives an average of EUR8.79 of collected VAT per declaration. These data should not be taken as indicative of the volume of work carried out by the customs authorities, and general conclusions based on them should not be drawn about the importance of e-commerce for Customs. As already mentioned, in addition to their fiscal function, Customs has other tasks assigned, the implementation of which in such importations is very difficult.

Of interest is the distribution of low-value consignments according to the way they are declared for release into free circulation. In the first year of implementation of the new import VAT rules, more than half the consignments (57 per cent) had customs duty imposed on the use of the special arrangement. The IOSS regime, considered the most efficient and easiest way to declare, ranked second and was used for 29 per cent of the consignments, while the standard import procedure was used for 15 per cent of the consignments.

The number of processed SADs by type of declaration regime by month for the period 1 July 2021 to 30 June 2022 shows a decreasing trend in the processed SADs (H7) for the special arrangement and an increasing trend in the share of those under the IOSS regime (Figure 4). At the beginning of the period the difference between the two regimes is notable (over 20,000 consignments), while at the end the difference is below 5000 consignments. This may be because an increasing number of third country online merchants are now registered for the EU IOSS regime, thus expanding its scope (currently their number is more than 8600). The relative stability in using the standard procedure is apparent, which may be the result of users not being familiar with the other two options or the more conservative attitude of online users.

The analysis based on the declared customs value in the processed SADs (H7) shows results similar to Figure 4, with the special arrangement (54 per cent) taking the lead here as well (Table 1). The IOSS regime has seen some decline, accounting for only 23 per cent of the total value of low-value consignments. This decline is mainly due to an increase in the standard procedure, which occupies a share of 23 per cent. Essentially, these data are difficult to analyse, due to a lack of information on the type of declared goods and the tariff numbers.

In terms of the dynamics of the processed SADs (H7) by types of declaration regimes according to the declared customs value by months for the period 1 July 2021 to 30 June 2022, the same development of the standard procedure and the IOSS declaration regime can be seen, with the latter showing a slight growth. Despite its dominant importance in terms of the value of consignments processed, the special arrangement reported a decline (Figure 5).

The two main channels for customs clearance of goods – for standard consignments, usually B2B in nature and of significant value or volume, and for certain categories of consignments, such as postal and courier consignments containing goods of value below a certain threshold (de minimis) (Blegen, 2020) – are clearly distinguished in the EU member states. The comparison of these two channels based on the available data also shows interesting results that lead to conclusions about the importance of cross-border e-commerce for Customs in the Republic of Bulgaria (Table 2).

The data in Table 2 show the number of processed consignments and the total value of goods released for free circulation in the country during the period 1 July 2021 to 30 June 2022. It is evident from the data that in terms of the value of the goods, it cannot be claimed that the import of low-value consignments is of notable importance, as it only accounts for 0.078 per cent of the total imports for the period. At the same time, the data on the number of processed customs declarations under column H7 unequivocally show that the processing of these consignments requires a lot of administrative customs resources. Their share of just over 37 per cent is substantial and therefore it is necessary to provide Customs not only with appropriate IT solutions, but also with human resources. Although the declaring and processing of customs declarations under the IOSS regime is largely automated, the other two declaration regimes under column H7 require some intervention by customs officials. If we add the need to carry out physical checks on certain consignments and the time for their customs clearance, the necessary resources for this increase significantly. Despite the use of risk analysis as the main method for the selection of consignments, control in terms of security and safety requirements represents a major challenge for any customs system.

The data in Table 2 on the dynamics of the SADs processed for the period 1 July 2021 to 30 June 2022 show relative stability in the number of declarations under column H1 for the ‘release for free circulation procedure’ (code 40), varying around 40,000 on average per month (Figure 6). For the SADs under column H7, the dynamics are more variable, and even a slight downward trend is observed for the period 1 July 2021 to 30 June 2022.

The main purpose of the new VAT rules on importing low-value consignments into the EU member states is to reduce administrative obstacles for importers and the amount of lost revenue because of fraud. At the same time, the costs of physical examinations of the goods should also be considered, which in certain cases can be greater than the potential VAT revenues. A fact that cannot be underestimated is that in most cases the recipients of small consignments are not well acquainted with customs formalities and this leads to additional problems and delays in processing the consignments. This necessitates the development of effective mechanisms to ensure that customs control in the member states is properly implemented.

7. Conclusion

The long-standing problem of fraud in the EU regarding the import VAT on postal and courier consignments has led to a change in the regime for levying this tax in the EU, which came into force on 1 July 2021. The new rules also involve new customs formalities, covering the import of consignments with an intrinsic value of up to EUR150, with three options already used for customs clearance of their import.

Although only one year has passed since the new VAT rules entered into force, three main points can be made:

-

The new EU VAT rules on cross-border e-commerce of low-value consignments have led to several simplifications both for sellers and importers, and for customs authorities, and are aimed at overcoming the long-standing problem of tax evasion when importing such goods. Customs clearance options are introduced, which provide different opportunities and advantages for all stakeholders – sellers, buyers and control authorities.

-

The new rules present Customs with several challenges, which are currently assessed as difficult to overcome. Potential problems such as undervaluation of goods, incorrect tariff classification, smuggling, infringement of intellectual property rights, wrongful collection or incorrect payment of VAT and refusals to accept consignments by EU recipients should be adequately addressed through risk analysis and the increased use of information technology.

-

Directly applying the European law, the Republic of Bulgaria has adopted the new VAT rules, as over the past year both the customs administration and online users have had to adapt to them. Most Bulgarian users use the special arrangement for declaring their import consignments, which could be because a small number of the electronic platforms and the third country providers they use still have a European IOSS number. At the same time, the relatively large number of processed SADs under column H7 requires additional administrative resources on the part of the Bulgarian customs administration, which would allow the proper implementation of the fiscal and security functions assigned to it.

Note

Consignments containing goods whose intrinsic value did not exceed a total of EUR22 (for Bulgaria the limit was BGN30) were not subject to customs duties and VAT, and consignments containing goods whose intrinsic value did not exceed a total of EUR150 were exempt from paying duties but were not exempt from paying VAT (Article 23 of Council Regulation (EC) No. 1186/2009 of 16 November 2009 setting up a Community system of reliefs from customs duties).

Pursuant to Article 9, Paragraph 2 of Council Decision 2020/2053, member states shall retain 25 per cent of the amount of customs duties collected on their territory as compensation for the administrative costs incurred in collecting them, and the rest constitutes the so-called ‘traditional own resources’.

Foreseen in Article143a of the Union Customs Code-Delegated Act (UCC-DA), the so-called super reduced dataset contains a set of data requirements meant to facilitate the implementation of the customs aspects of the VAT e-commerce package. The detailed content (data set) of this particular customs declaration is defined in Annex B of the UCC-DA under column H7. Customs declarations containing the H7 data set can be used: (a) by any person, (b) for goods sent in B2C, B2B or C2C consignments up to an intrinsic value of 150EUR subject to customs duty exemption in accordance with Article 23(1) DRR or in C2C consignments up to an intrinsic value of 45EUR subject to customs duty exemption in accordance with Article 25(1) DRR and (c) for IOSS, special arrangements or the standard import VAT collection mechanism.

EORI is a registration and identification number of economic operators and natural persons, used in all activities covered by customs and excise legislation applicable throughout the European Union.

For example, the standard VAT rate in Bulgaria is 20 per cent. If the importer sets the system to charge 21 per cent, this harms the buyer, who may not pay attention to the VAT charged. Thus, the buyer transfers 20 per cent VAT to the tax administration, but the one per cent difference remains with the importer. Since the amounts are small, it is unlikely that the buyer would appeal them.

_by_types_of_declaration_regimes_for_the_peri.png)

_by_types_of_declaration_regimes_according_to_declared_cust.png)

_by_types_of_declaration_regimes_for_the_peri.png)

_by_types_of_declaration_regimes_according_to_declared_cust.png)