1. Introduction

While issues regarding the low level of female representation in Customs and elsewhere are now evident, the crucial roles that female officers and leaders play in supporting customs modernisation should be highlighted. In 2021 during the online event ‘Women in Customs’, Dr Kunio Mikuriya, World Customs Organization (WCO) Secretary General, stated that a gender-diverse and inclusive workplace contributes to an innovative and high-performance organisation as various contributions and perspectives from all genders and backgrounds are necessarily needed for growth in Customs (WCO, 2021). This means that customs administrations should advance and include female officers in decision-making if they wish to modernise their organisation innovatively and effectively.

Gender equality is a global issue, and gender inequality in customs administrations exists almost everywhere. A survey conducted by the WCO in 2016 shows that globally, the percentage of female officers and leaders is approximately 36 per cent and 30 per cent, respectively (Törnström, 2018). These figures (Törnström, 2018) range from 8 per cent to 60 per cent based on country and region. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) states that the percentage of female officers in law enforcement agencies in Southeast Asia is low, and that the agencies are still largely occupied by men (UNODC, 2021a). According to a study by UNODC, UN Women and Interpol (2020), the number of women employed in law enforcement agencies in Southeast Asia is between 6 per cent and 20 per cent, which is very low compared to the global figure.

This paper highlights how advancing and including women enables innovative and effective customs modernisation. It also assesses the rationales behind the low representation of female officers and leaders in Customs by identifying the challenges women face in Southeast Asia in acquiring management positions. The paper explores international best practices and successes in advancing and including more women in customs leadership. Finally, it suggests practical recommendations to support and advance women for a gender-inclusive Customs in Southeast Asia and other administrations around the globe with similar challenges and situations.

The paper involves both qualitative and quantitative methods. Data sources are from existing secondary sources and previous surveys conducted by Hong et al. (2022) and the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) University Transnational Security Centre (2021). The survey conducted by Hong et al. (2022) provides information on the opinions of female customs officers in Cambodia and Indonesia, while the survey conducted by RMIT University Transnational Security Centre (2021) provides some overview and opinions from female customs officers from many Southeast Asian countries, including Cambodia, Thailand, Philippines, Laos, Vietnam, Indonesia, Laos and Malaysia.

2. A gender-inclusive Customs

2.1. Achieving sustainable development and growth

Gender inclusiveness and equality have been claimed by many international organisations to be an important factor in organisational development. The UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights highlights that gender equality and diversity are the key to achieving sustainability of growth and innovation in all administrations (WCO, 2022). The UN outlines that equal representation of women in decision-making related to politics and economics is one of the objectives in the Sustainable Development Goals (UN, 2022) and one of the priorities in the UN Sustainable Development Agenda for 2030 (UN, 2015). The WCO recognises the necessity of gender equality by placing it as one of the prime concerns in its capacity building agenda to improve the performance of customs administrations (WCO, 2022). In addition, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) commits to empower women to recognise their potential to create innovation, employment, economy and fair decision-making (OECD, 2015). The World Trade Organization (WTO) acknowledges the benefits of including both gender perspectives, having gender-responsive policies, and that eliminating constraints for women in trade can lead to sustainable social and economic development (WTO, 2017). Furthermore, the UNODC believes that gender parity in the workplace can increase the organisation’s performance in promoting trust, the rule of law, the fight against crime, and in the protection of society and the community. Therefore, workplaces need to review their personnel regularly to see if their organisation has gender-balanced employees, enabling an adaptive and diverse staff composition (UNODC, UN Women and Interpol, 2020).

Globally, many inspiring leaders in Customs have shared their strong beliefs and emphasised the benefits of gender equality in the development and growth for customs administrations. For example, Commissioner Shane Fitzsimmons (2021), from Resilience New South Wales, states that if customs administrations do not provide opportunities for women officers and leaders to be present at all levels, the administrations will miss 50 per cent of talented people (S. Fitzsimmons, personal communication, 25 August 2021). Mrs Yeo Beng Huay, Chief Information Officer of Singapore Customs, believes that providing the same sets of opportunities both in the workplace and outside the workplace contributes to enhancing productive outcomes and unity at work, which are vital to economic growth and social harmony (Singapore Customs, 2020). Jeremy Douglas, UNODC Regional Representative for Southeast Asia and the Pacific, also emphasises that promoting women officers provides several advantages to the countries in Southeast Asia and provides enforcement agencies with the capability to better respond to the various crime issues in the region (UNODC, 2020).

2.2. Addressing the diverse issues facing Customs

Customs administrations need both genders to solve the different issues they face. Women often have the specific skills and professional qualities that are crucial for administration modernisation and growth, despite the fact that customs administrations are mostly dominated by men (Hall & Oliver, 2013). Firstly, in general, women have advanced interpersonal communication skills, use less excessive force than men, and have outstanding problem-solving abilities with an eye for detail, which makes them effective in addressing certain types of crimes or offences (Fritsvold, n.d.). This means that both male and female officers are desirable to solve the different types of crimes and violations seen by the law enforcement profession, including Customs.

Secondly, female officers can contribute to gaining the public’s trust, and reducing corruption − a key aim of the governments in the Southeast Asian region (UNODC, 2020). Women are more easily trusted and able to gather intelligence as they are more approachable and responsive to the needs of female citizens who may be susceptible to fears and sexual harassment by men (UNODC, UN Women and Interpol, 2020).

Thirdly, having a 50:50 gender ratio in the workforce is the best approach to provide the best public services for society that generally comprises 50:50 female:male citizens (UNODC, 2020). Furthermore, without female officers, it is rather difficult to deal with the concerns of other women in the community (UNODC, 2020). In other words, female customs officers and leaders may be able support and address the concerns of women traders where male customs officers may not. European Commission (EC) Director Sabine Henzler emphasises that without sufficient female officers, customs administrations would have limited practical experience to address women’s needs and circumstances (EC, 2021).

2.3. Increasing safety in the workplace

Including more women in Customs and in leadership positions allows women to protect each other and supports the involvement of more women in trade. Female traders will feel safer and more secure if they are surrounded by other women during goods clearance. Female traders have faced issues at customs borders, including limited safety and potential sexual harassment (US Agency for International Development, 2021). Having more female officers will ease the challenges facing female traders. In particular, if the female officers are in leadership roles, they will have more power to enforce policies protecting female officers and traders, which contributes to safety in the workplace overall.

3. What are the challenges facing female officers and leaders?

While the significant positive impact of female officers and leaders has been discussed and acknowledged, women are still underrepresented in Customs. According to an OECD report, the number of women assigned to senior government positions remains low (OECD, 2014). Based on the literature and the survey by Hong et al. (2022), there are several reasons for this, ranging from cultural barriers to physical ability.

3.1. Cultural barriers

Cultural norms seem to affect the current situation of women in Southeast Asia (Friedrich Naumann Foundation, 2020). Firstly, women are still expected to take responsibility for all household tasks (Hong et al., 2022). This means that whether they have a job or not, they remain responsible for caring for the house and managing all the chores. They must ensure that their home is in order before they can start focusing on their work. Therefore, due to these constraints, some female officers stated in the survey by Hong et al. (2022) and in the study by RMIT University Transnational Security Centre (2021) that they find it hard to even think about their professional development. They also mention in both surveys that if they are married, they must take care of their children and/or sometimes the elders of the household, leaving very little room for them to improve themselves professionally.

Secondly, the surveys indicate that it is unlikely that women are expected to be ambitious in the workplace. The culture in Southeast Asia still places an expectation on men to succeed in their work while women support their husband by taking care of the family. This expectation holds women back from following their education and professional ambitions as well as allowing people to question their capability at work (Tan, 2016). The success of women is not expected at the workplace but at home. In addition, societal perspectives based on traditional Asian culture do not encourage women to work in law enforcement as this job is seen to be more suitable for men (UNODC, 2020).

3.2. Gender stereotypes

Gender stereotype is an unconscious bias and one of the challenges women in the workplace face, including in Customs. In general, in both surveys, more women in Southeast Asia express that they have observed this issue than in other regions. Firstly, women are generally viewed as emotional, sensitive people who cannot make the big decisions that require a tough, strong mind (Bauer, 2015). There is often the perception that some positions require certain characteristics that are seen to be inherent to each gender (Silva & Davis, 2020). This means that due to the perceived inherent caring and soft nature of women, they are easily affected by outside factors, so may be perceived by others to not be suited to leadership positions, which require tough, strong minds, like those of men.

Secondly, some survey respondents mention that women’s voices are not really heard in meetings. Women are usually included in meetings as secretaries or for logistics arrangements only (Hong et al., 2022). Even though there is a general trend to include women, they are mostly confined to desk and administrative work. Women recruited to law enforcement are normally assigned to administrative jobs rather than decision-making or leadership positions (UNODC, 2021a). A male-dominated organisation is very likely to ignore women’s voices and representation; therefore, the decisions are not inclusive, while leadership opportunities for women are rare (United States Agency for International Development, 2021).

Thirdly, there seem to be certain myths about women’s capabilities. Some female respondents mention that women are not considered suitable for certain important tasks. This means women sometimes lack support both from men and other women. For example, Colonel Portia Manalad mentions that she faced several challenges, one of which was that she had to prove herself by working twice as hard as men (Schmidt, 2019). This could be a hidden barrier that women may not normally talk about, but they have actually experienced in the workplace, including Customs. A female customs officer, Maria Cristina Fuentes from Philipines Customs, also shared her experience where she was not initially included in customs operations to the same extent as the men; therefore, she had to put a great deal of effort into proving her abilities (Schmidt, 2019). In addition, speaking of leadership roles, most people seem to expect men to be leaders while women serve as supporters or followers. A few survey respondents think that leadership roles require significant effort and the capability to handle pressure, which are unsuitable for women, in their view.

3.3. Lack of confidence

According to the surveys, lack of confidence seems to be one of the main barriers for women in Customs. Firstly, most female officers in Southeast Asia said that they are unwilling to take the same risks as men. Instead, they would prefer to stay in their comfort zones due to fears about many things in their personal life. Secondly, some female survey respondents do not believe that they have the capability or the capacity to follow their dreams. Sandberg (2013) states that women often undervalue themselves and their abilities, while men seem to overestimate their abilities. Because of this, women seem to miss many promotion opportunities as they are constantly questioning themselves. Without confidence in themselves, women may find it hard to make other people believe in them.

However, issues related to this lack of confidence may stem from cultural norms and gender stereotypes. If people in their homes and workplaces believe women are less capable, this will affect women’s confidence in themselves. This lack of confidence may stem from long-held beliefs and not from the women themselves. Therefore, this barrier needs to be addressed if Customs wants to promote women.

3.4. Limited physical ability

Some research and surveys include women’s physical ability as a barrier for women in law enforcement, including Customs. Firstly, customs administrations have many offices at borders, which may be isolated and may be regarded as relatively unsafe for women. Due to their perceived limited ability to defend themselves, women are generally not assigned to isolated border posts. More than 60 per cent of survey respondents mention that they are not selected for certain positions due to this barrier (Hong et al., 2022). This alone limits the representation of women at customs offices, which accounts for the majority of customs positions.

Secondly, customs offices at the border require some officers to be on standby 24/7. This kind of job is not ideal for many women due to safety issues. Moreover, many married female officers must return home early to take care of children and family and are not comfortable staying away from home overnight (US Agency for International Development, 2021). UNODC states that such a barrier is one of the main reasons that law enforcement agencies find it hard to advance women leaders (UNODC, UN Women and Interpol, 2020). Law enforcement agencies require their officers to work full-time without interruption, while women may have many responsibilities at home that require much understanding and flexibility in the workplace (UNODC, UN Women and Interpol, 2020). Physical strength is still preferred in law enforcement. Women must act like men if they want to break down these barriers (UNODC, UN Women and Interpol, 2020).

4. What are the best practices and success stories internationally?

Many international organisations, including the WCO, the UN, and others, have developed global policies to support customs administrations to address gender-related issues, while many customs administrations have successfully expanded policies to include and advance women officers and leaders.

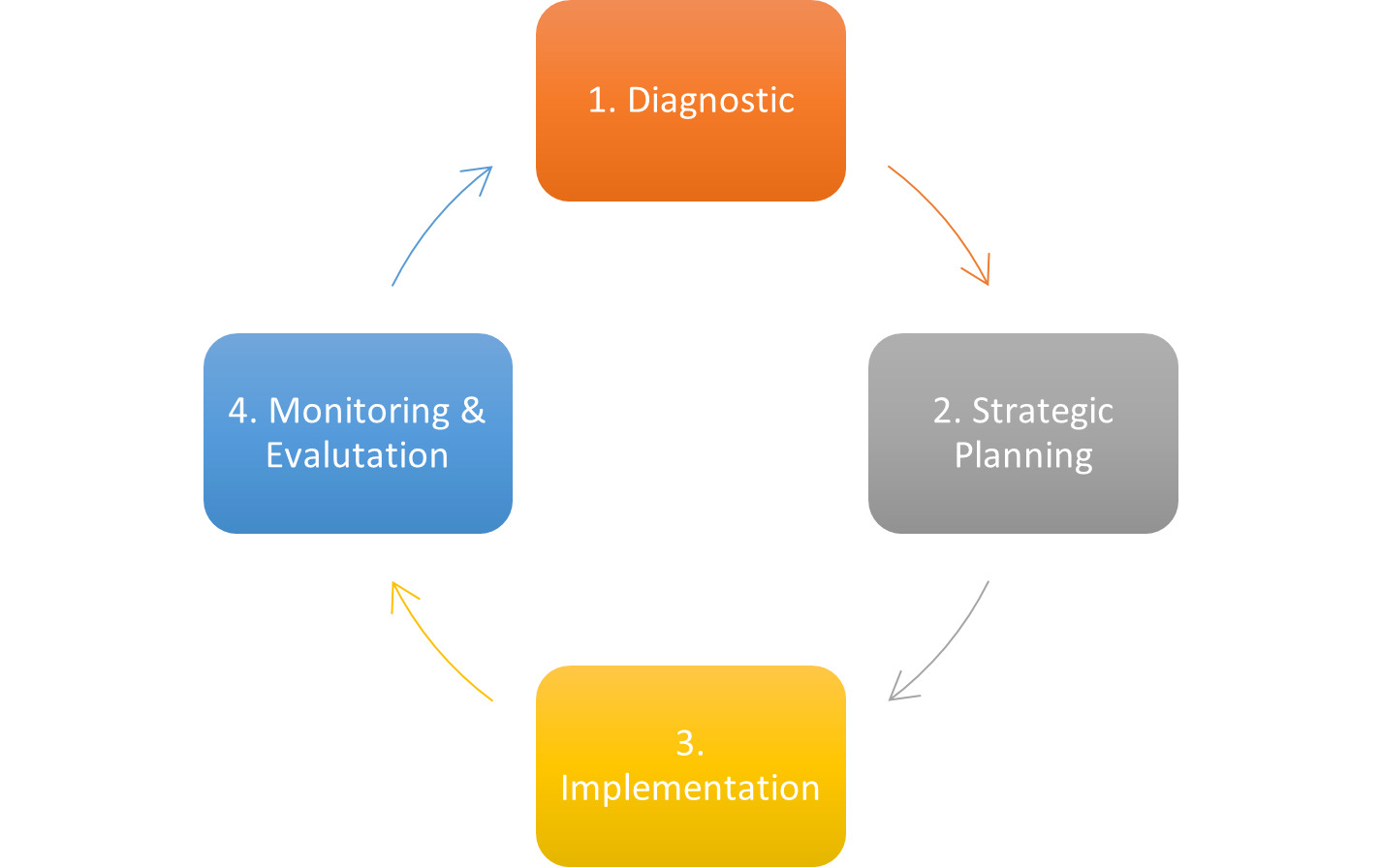

The WCO created the Gender Equality Organizational Assessment Tool (GEOAT) to support customs administrations in assessing their current policies and practices to identify issues related to gender equality and resolve plans or projects to be included in the transformation plan of their administrations (WCO, 2019). Figure 1 illustrates the project cycle approach to implement gender mainstreaming[1] for Customs reform and modernisation.

The WCO adopted the Virtual Working Group for Gender Equality and Diversity to establish an exchange platform for members to communicate their experiences, activities and discuss the use of GEOAT (WCO, 2021). The WCO calls for a holistic approach in dealing with gender equality and inclusiveness issues by developing internal and external policies (WCO, 2021). Internal policies focus on including women in management and leadership and advancing women in professional development; external policies focus on gender inclusion when collaborating with stakeholders and working at the border (WCO, 2021).

Regarding UN initiatives, the Women’s Network of Container Control Programme (CCP) was created in 2015 to support women’s representation in the CCP programme and encourage meaningful and new conversations about women in law enforcement (UNODC, 2022). All women working in Port Control Units (PCUs) and Air Cargo Control Units (ACCU) are part of this large network that provides several opportunities for women in Customs (UNODC, 2022). One of the recent innovative successes of this network is the implementation of the CCP Women’s Professional Development Programme, with the cooperation of the Australia Border Force (ABF) and RMIT University (UNODC, 2021b). This programme offers an incredible opportunity for female customs officers to advance their leadership skills, learn customs-related knowledge and network with other female officers and leaders in Customs from 11 countries in South Asia, Southeast Asia and the Pacific (UNODC, 2021b). Based on the programme feedback, participants reported that there has been an increase in their confidence and willingness to be leaders and influencers in their organisation, and they have finished the programme with a new mindset and more substantial capabilities (Dodds et al., 2022). However, the programme is limited to the female customs officers involved with the CCP. Such an innovative programme is a great example to other customs administrations wanting to advance the position of women in their organisations.

Several countries have developed comprehensive policies to promote women in their customs administrations. For example, based on the WCO Compendium on Gender Equality and Diversity in Customs (WCO, 2020), Australia has been doing well in including more female officers and leaders. Behind this success, the Australian government, including the ABF, has launched several activities to support gender equality, including a breastfeeding-friendly workplace, the inclusion of women’s representation in every forum and internal boards and committees, and continuously reviewing and upgrading current policies to promote gender inclusiveness and equality based on emerging academic research. Due to this commitment, WCO (2020) highlighted that women officers accounted for 53.3 per cent of board positions in the Home Affairs Portfolio in 2019. Moreover, the Australian Department of Home Affairs has adopted the Staff Advancing Gender Equality (SAGE) Network to promote equal representation of women and men at all levels and encourage new discussion, meaningful changes, and women empowerment via emotional connectivity. In March 2022, the foreign minister of Australia at the time, Marise Payne, also stated that public policy shall include women’s contributions and voices, especially in planning to address the pandemic (Minister for Foreign Affairs, 2022).

Another good example is from the New Zealand Customs Service (NZCS), which has put the utmost effort into promoting gender equality (WCO, 2020). The NZCS started by raising awareness of the advantages of including and advancing women in the organisation. When a survey they conducted showed that realisation and acknowledgement of these advantages were established, the NZCS created the Inclusion and Diversity Council and developed a five-year strategic plan from 2014 to 2018. Several activities in the strategic plan led to success. For instance, actions to promote women in leadership roles resulted in an increased number of female leaders, from 24 per cent in 2014 to 32 per cent in 2018. According to the survey conducted by the NZCS, this initiative and its fruitful results have been greatly supported by respondents, who were very pleased and satisfied by the results. Furthermore, in its 2019 to 2021 strategic plan, the NZCS has put more efforts into gender equity to support and promote women further by committing to reaching at least 36.5 per cent of women leaders. The figure illustrates the firm commitment that the NZCS and NZ government have placed on promoting women and the value that women can bring to the organisation.

Many customs administrations in Southeast Asia have launched initiatives to promote existing female officers in their organisations. The administrations have developed gender equality and inclusiveness working groups that work directly to promote and advance women. For example, the General Department of Customs and Excise of Cambodia (GDCE) has established a women’s association in Customs to support female officers in overcoming family- or work-related barriers and to ensure that female officers receive the same opportunities as men and are not excluded in any circumstance (GDCE Women’s Association, 2021). Similarly, the Philippines Bureau of Customs (BoC) has established a Gender Focal Point System to lead gender policies and plans, and the BoC commits to employ 5 per cent of resources annually for gender-advancing activities (Philippines BoC, 2022). Ms Marilou A Cabigon, Collector of Customs Vice-Chairperson of the Philippines BoC (2022) states that customs administrations need continuous resources to put planning and policies into practice and to ensure sustainable and effective delivery of any gender initiatives.

Worldwide, many female leaders in Customs have shared their top tips behind their success and how they overcame barriers to climb the career ladder. One great example is Mrs Yeo Beng Huy, a Chief Information Officer of Singapore Customs. She stated that the support from family, managers and her team were key to her success in overcoming obstacles along the way (Singapore Customs, 2020). Moreover, being able to work with several other successful female leaders was motivating and inspiring (Singapore Customs, 2020). Similarly, Major Dr Mac Xuan Huong of the Vietnam People’s Police Academy states that women are inspired by the examples set by their female mentors and by those women who make them believe that they can achieve their aims (UNODC, 2021). Another great insight is from Deputy Chief Shannon Trump of the Noblesville, Indiana Police Department and Kym Craven, Executive Director of the (US) National Association of Women Law Enforcement Executives, who recommend women choose a favourite mentor who can support and guide them to break through barriers and find ways to achieve their career goals (Fritsvold, n.d.). By receiving the support they need, women do not need to limit themselves and can build the confidence and belief in themselves to make it big in life (Fritsvold, n.d.). Ta Thi Bich Lien and Suchaya Mokkhasen, UNODC Programme Officers, also express similar insight − having women who support other women in the workplace is very significant for gender equality (UNODC, 2021).

5. Recommendations

After acknowledging the necessity to capitalise on diverse genders and backgrounds, this paper has some recommendations to advance women for a more gender-inclusive Customs. It is important to note that adding more female officers in law enforcement, including Customs, is a key step, but it cannot be the only step for female officers, especially in Southeast Asia, as additional instruments and policies are needed to break the barriers facing women and to promote a secure environment where women can grow, engage and advance in their careers (UNODC, 2020).

5.1. Assessing the current situation and the ways forward

Diagnosing the current situation related to gender equality and inclusiveness is the first key step that all customs administrations should take. Administrations that have not assessed their current status can contact the WCO to ask for assistance in evaluating the current situation regarding gender equality, identifying gaps in the current policies and practices and then developing relevant policies or project planning to address the identified challenges. Knowing their current status and where they need to make changes allows customs administrations to work closely with the WCO, using the essential tools provided by the WCO, to advance women to transform and modernise Customs effectively and successfully.

5.2. Incorporating gender mainstreaming in recruitment and promotion

Customs administrations should include gender mainstreaming in recruitment and promotion. For example, in the recruitment process, customs administrations should use gender inclusive language in the vacancy announcement to encourage both genders, especially women, to apply. Simply including the value statement ‘women are encouraged to apply’ can help make a tremendous impact on the number of women who will apply (UN Women, 2022). Since women tend to underestimate themselves and lack confidence, such encouragement would support breaking these barriers and changing their mindsets about applying to work in customs administrations. By doing this, customs administrations are likely to receive more qualified women than they otherwise would expect. Regarding staff promotion policies, customs administrations can consider whether they have adequately qualified female leaders. If not, what support do female officers need to become adequately qualified for promotion? When administrations do not have qualified women who deserve a promotion, it may be a red flag that there is a gender issue that needs addressing.

By considering these factors, customs administrations can increase the number of female officers and leaders and improve the organisation’s outcomes and performance. When customs administrations have more female leaders, other women are inspired to achieve success like them (US Agency for International Development, 2021). Hong et al. (2022) mention that women cannot become what they cannot see with their own eyes. There must be role models for them to see that it is possible for women to succeed and acquire leadership roles.

5.3. Establishing policies to support women in Customs

Customs administrations need to establish policies that support existing female staff and ensure that those policies are gender-friendly and inclusive.

Customs administrations can consider developing a mentoring program for women. Anyone who wants to support women can volunteer to become a mentor, and women can request a mentor that fits their needs. Mentors can be both men and women as long as they express a clear intention to help women grow. If such a system is in place, many customs leaders may be willing to show and offer their support. A joint UNODC, Interpol and UN Women study indicates that having a mentor and the support of male staff, especially leaders with a lot of power and influence, is essential to women’s advancement and promotion in law enforcement (UNODC, UN Women and Interpol, 2020).

Customs administrations can consider adopting gender-inclusive initiatives and ensure the sustainability of those initiatives by having gender diverse decision-making, outlining clear roles and responsibilities that respond to the needs of the trading community (OECD, 2014). Based on the survey results (Hong et al., 2022), respondents from Southeast Asian countries express strong support for such gender-based policies, including male champions, which offer support for women in the workplace.

5.4. Regularly implementing professional development programs for women

The availability of professional development programs for women within the organisation is a key aspect to advancing women and unleashing their potential. Such programs should explore the barriers and challenges of each woman to discover what is happening in their lives and how the organisation can help support them in the workplace. The programs can include motivational speakers who will empower and inspire the female officers to realise their potential and ability, which is necessary for them to set their career goals and work hard to achieve them.

The programs should be offered regularly and be available to all women in the organisation. The programs should be implemented regularly to ensure that new female officers can benefit from them as soon as possible. Women who have shown strong motivation and dramatic growth due to the program can become in-house trainers to train other female officers. Male leaders can also become trainers to support women. In addition, senior female officers or female leaders can share their knowledge and experience with junior female officers, which would highly relevant to them and thus very valuable (UNODC, 2021).

Customs administrations can consider developing such a program on their own or design a program plan and seek support from development partners such as WCO, UNODC, ABF and many other development partners who are passionate about developing and advancing women in customs.

6. Conclusion

Gender equality and diversity in Customs is not only an issue of morality, it is about the need for customs modernisation and sustainable development. It is already well-acknowledged worldwide that gender-inclusive workplaces, including Customs, are undeniably important. While customs administrations around the globe, including the Southeast Asian region, have implemented several initiatives and activities to support women, global facts and figures remain far from targeted parity. Women in Customs, particularly in Southeast Asia, still face common challenges including cultural norms, gender stereotypes, lack of confidence and perceived limited physical ability. Before customs administrations can reap the benefits that women can bring to the table, they need to adopt new policies to address and remove the barriers that prevent the advancement of women.

It is time to draw more attention to this issue and raise awareness among customs administrations worldwide by highlighting the advantages of including more women in Customs at all levels, discussing the barriers they face, and exploring how customs administrations can help them break these barriers to include them effectively. The successful experiences of inclusive customs administrations can act as role models for best practices. When customs administrations have an in-depth understanding of their current situation and the reasons why they should include and empower more women, they are more likely to establish the policies needed to become modern, inclusive, and more innovative administrations.

Gender mainstreaming refers to the process of including and considering diverse perspectives from both genders at all stages of policy development and implementation (WCO, 2021).