1. Introduction

The WTO has established a corpus juris to regulate global trade among its members. GATT 1994 (GATT, 1994) governs trade in goods to ensure that global trade is conducted in accordance with agreed rules. A key principle in global trade is the most-favoured nation (MFN) rule that lays down a fundamental principle of non-discrimination among WTO members. However, Article XXIV of GATT 1994 (hereafter Article XXIV), provides for the formation of FTAs and customs unions (CUs) whose operations can, within certain limits, deviate from the MFN rule. Since the end of World War II and the signing of GATT 1947, world trade has witnessed a gradual increase in the number of FTAs. As at 1 June 2023, a total of 303 FTAs had been notified to the WTO under Article XXIV (WTO, n.d.-a). Although these FTAs are regional in nature, they serve as major building blocks towards the liberalisation of global trade (WTO, 1994).

This paper explores the relevance and the role that Customs[1] plays in the operations of FTAs. It therefore examines the generic functions of Customs and uses these to assess how they relate to the operations of FTAs.

2. Generic functions of Customs

The role of Customs in any country is dictated by its own priorities and national laws. In general, the functions of Customs include revenue collection, protecting national security, controlling imports and exports by ensuring that international trade complies with national laws, protection of domestic industry against imports, implementing laws to ensure that trade complies with international obligations under the WTO, and safeguarding the security of the supply chain involving the movement of goods in international trade (De Wulf, 2005). It therefore follows that the structures of customs administrations at national levels will be determined by the roles as stipulated by domestic statutes.

By operating at the borders and processing imports and exports, Customs has an impact on trade facilitation. It must be noted, however, that implementation of trade facilitation measures is not the exclusive domain of Customs, although admittedly, it is a major player[2]. Bureaucratic customs administrations with outdated or uncoordinated laws and procedures can hamper trade and destroy the very reason why FTAs are created. In this regard, while most customs administrations fall under the government ministry responsible for fiscal matters, they implement and enforce several policies on behalf of other government agencies, such as foreign trade and agricultural controls.

The World Customs Organization (WCO) prioritises trade facilitation, and it collaborates with the WTO in implementing international trade instruments. The WCO has stated:

[…] Trade facilitation, in the WCO context, means the avoidance of unnecessary trade restrictiveness. This can be achieved by applying modern techniques and technologies, while improving the quality of controls in an internationally harmonized manner.

The WCO’s mission is to enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of Customs administrations by harmonizing and simplifying Customs procedures. This in turn will lead to trade facilitation which has been a genuine objective of the WCO since its establishment in 1952 […] (WCO, n.d.-a)

The above statement clearly spells out that the facilitation of trade is one of the principal missions of the WCO. During negotiations on the WTO’s Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA), the WCO was a key participant and represented the global voice of Customs by providing input on practical issues (WCO, n.d.-b). This demonstrates how the WTO and the WCO work together to promote international trade. The collaboration is cemented when considering that their definitions of trade facilitation are the same.

One of the key functions of Customs is revenue collection. To cater for those with a strong orientation towards revenue collection, such customs authorities need to ensure that they acquire the relevant skills in revenue collection and its management. Other customs jurisdictions place emphasis on state security and border control, and for such, the strength would be to have requisite skills in military and policing in place. It is therefore evident that in addition to levying customs duties, customs laws also govern imports and exports and any issues involving the cross-border movement of goods. Customs has strengthened its security function by adopting the WCO’s SAFE Framework of Standards to Secure and Facilitate Global Trade (SAFE Framework) of 2005 (Rogmann, 2019). The SAFE Framework sets out operational standards based on cooperation, resting on three pillars: customs administrations themselves, Customs and its business stakeholders, and Customs and other government agencies (WCO, n.d.-c).

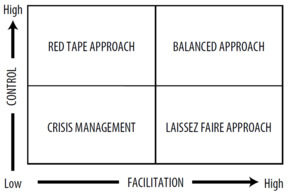

An efficient customs administration must thus attain a balance between its various functions, some of which may appear to be mutually exclusive. This is a crux for customs administrations, in which professional expertise is required to balance these roles. Widdowson (2005) compared the two variables of control and trade facilitation and, as shown in Figure 1, he identified possible scenarios, represented by the four matrices as indicated. It shows the important role that Customs plays in facilitating trade, without compromising its security and control function. The desired equilibrium is the ‘Balanced Approach’ in which both the Customs functions of control and trade facilitation are high (Widdowson, 2005). As reflected, any other scenarios result in ‘Red Tape’, ‘Crisis Management’ or ‘Laissez-Faire’ approaches, all of which compromise the functions of Customs.

Figure 1 therefore demonstrates that Customs is not a straitjacket function but involves delicate balancing of many roles and skills. The depth and breadth of customs work has become more complex and will continue to become more complicated as it responds to developments in the environment, for example, economic, sociocultural and technological developments. Regional and global trade will continue to influence Customs. Customs authorities will need the skills to remain relevant and successfully discharge their duties.

3. Definition of FTA

The nature of operations of an FTA can be deduced from its definition. An FTA involves the movement of goods across borders, and arising from this, there are bound to be linkages with the role of Customs. Article XXIV:8(b) of the GATT (GATT, 1994) defines an FTA as follows:

A free-trade area shall be understood to mean a group of two or more customs territories in which the duties and other restrictive regulations of commerce (except, where necessary, those permitted under Articles XI, XII, XIII, XIV, XV and XX) are eliminated on substantially all the trade between the constituent territories in products originating in such territories.

The definition is important in that it is pronounced in the legal texts of the WTO and thus has legal effect. There are of course simplified explanations as captured in some published literature and books, including some from the WTO, but all these must be viewed as attempts to put legal terminology into plain language.[3] This paper will not examine the exceptions in Articles XI, XII, XIII, XIV, XV and XX, which also apply in relation to CUs.[4]

Further to the definition of an FTA, it must be noted that Article XXIV:4 stipulates the goals of an FTA, and states that:

The Members recognize the desirability of increasing freedom of trade by the development, through voluntary agreements, of closer integration between the economies of the countries parties to such agreements. They also recognize that the purpose of a customs union or of a free-trade area should be to facilitate trade between the constituent territories and not to raise barriers to the trade of other contracting parties with such territories. (GATT, 1994)

From this provision, it can be noted that the whole purpose of an FTA is to expand and facilitate trade among its members. This is consistent with the idea that one of the goals of Article XXIV is to make FTAs a step towards free global trade rather than to create hurdles to the expansion of multilateral trade. As a result of this, when entering into an FTA, the members must not create additional barriers with third parties. Most FTAs would however go beyond the basics of the tariff-free movement of goods and proceed to the harmonising of procedures and laws to facilitate the movement of goods within their membership. This original intention of the GATT was confirmed in the preamble to the Understanding on the Interpretation of Article XXIV of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (WTO, 1994), which states:

[…] Reaffirming that the purpose of such agreements should be to facilitate trade between the constituent territories and not to raise barriers to the trade of other Members with such territories; and that in their formation or enlargement the parties to them should to the greatest possible extent avoid creating adverse effects on the trade of other Members; […]

In summary, it can be noted that the constituent elements of an FTA are as follows:

(a) it must be comprised of at least two customs territories

(b) the purpose must be to facilitate trade among the participating members

(c) duties must be eliminated

(d) restrictive regulations must be eliminated

(e) liberalisation must apply to substantially all trade

(f) preferential trade applies to originating products.

The author considers that the above criteria is the rubric used to identify the existence of an FTA in the context of GATT 1994 and the WTO. Any trading arrangement that meets all the given elements is an FTA. In practice, compliance with all the above fixed criteria is a gradual process, not a single event. Parties to the WTO Agreement are obligated to adhere to Article XXIV and WTO rules in any trading arrangement they enter into. It should be noted that, in practice, the WTO has been liberal when dealing with the registration of FTAs, with some notifications having been done when the FTA had already entered into force.[5] The WTO has generally endorsed that the legal process of registering a FTA can even take place after its entry into force.[6] A typical example, noted by Mavroidis (2012), is the North American Free Trade Area (NAFTA), which was signed in December 1992, entered into force in January 1994, and the relevant WTO committee examined its consistency with Article XXIV, and was subsequently established in March 1994.

4. Relevance of customs administrations in an FTA

The six elements of an FTA identified above serve as the foundation for assessing the relevance of Customs in FTAs and, in some ways, demonstrate the role of Customs in FTAs. Each of them are of importance to customs operations.

4.1. Composition of FTAs

An FTA must consist of at least two customs territories. Article XXIV:2 defines a customs territory as follows:

For the purposes of this Agreement a customs territory shall be understood to mean any territory with respect to which separate tariffs or other regulations of commerce are maintained for a substantial part of the trade of such territory with other territories. (GATT, 1994)

From this it can be deduced that, in plain language, a customs territory is a geographic area that is bound by uniform customs laws and procedures. This can cover a single or group of countries. In practice, most of the members of an FTA would be sovereign states. The WTO Agreement also explains the extent to which the term ‘customs territories’ can interchange with ‘country’ but at the same time underscoring the fact that the correct legal word is ‘customs territory’.[7] This matter came up in WTO jurisprudence, where it was opined that the question was not whether it was a sovereign country, but rather if it possessed the status of a customs territory and thus qualified for full WTO membership.[8] An FTA can therefore take the form of a bilateral agreement as was the case with the agreement signed between the United States and Morocco in 2004.[9] It can also be a regional grouping as is the case with the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) which include four non-EU member states, namely Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland (EFTA, 2020). The essential element is that the members must be customs territories.

It is noted that in an FTA, each customs territory may continue to apply its own legislation and external tariff. There is no provision compelling the customs territories forming an FTA to apply the same customs laws, other than to ordinarily harmonise their customs or trade procedures as per the dictates expected in trade facilitation. The FTA is therefore comprised of different customs territories whose objective is to allow the free movement of qualifying products. This contrasts with a CU, whose constituent customs territories all apply a common external tariff (CET) and common customs laws. The harmonisation of laws and procedures is however one of the requirements for trade facilitation, although an FTA can operate with each partner implementing its own customs laws.

An FTA is therefore closely associated with Customs as demonstrated by the fact that the constituent elements are all related to Customs. Further, the unit of membership is based on a customs territory and not on independent political statehood. As already noted, a customs territory has unique characteristic of common customs tariffs and laws pertaining to trade matters. This demonstrates a linkage between an FTA and elements from Customs.

4.2. Purpose of a free trade area

According to Article XXIV:4, one of the key purposes of an FTA is to facilitate trade:

The Members […] recognize that the purpose of a customs union or of a free-trade area should be to facilitate trade between the constituent territories and not to raise barriers to the trade of other contracting parties with such territories. (GATT, 1994)

The creation of FTAs is therefore intertwined with the implementation of more favourable trade facilitation measures. This given purpose is an important declaration on why FTAs are created. As a result, trade within the FTA must be more liberalised than it was before the FTA’s inception. It is evident from this that the whole aim of FTAs is to liberalise and facilitate trade between their constituent members. The principle that an FTA is designed to facilitate trade among constituent members can be extended to imply that an FTA can devise more favourable trade facilitation measures to specifically benefit its members. According to Okabe (2015) several studies have shown that when an FTA creates a framework to facilitate trade among its members an increase in trade within the configuration is the result. One of the latest FTAs, the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), was established by the Agreement Establishing the African Continental Free Trade Area (the AfCFTA Agreement) to facilitate and boost trade amongst its members.[10] The AfCFTA has also demonstrated this, and it developed its own legal tools to boost and facilitate trade among its members.[11]

Most FTAs go beyond the basics of the tariff-free movement of goods and proceed to the harmonising of procedures and laws to facilitate the movement of goods within their membership. It therefore follows that an FTA can devise more favourable trade facilitation measures for its members. These more favourable measures and treatment can be justified as falling within the ambit of Article XXIV (United Nations Conference on Trade And Development [UNCTAD], 2011). FTAs have emphasised the importance of facilitating trade within their own configurations, with some, including the AfCFTA, having developed their own frameworks for the facilitation of trade. As a result, the trade facilitation measures within an FTA do not necessarily have to be an exact duplicate of the WTO TFA. More often than not, most trade facilitation measures implemented in FTAs apply to members, in as much as they do to non-members. The test will be whether such measures impose any additional burden on WTO members not participating in the FTA. Any formation of an FTA whose design does not facilitate trade, or which raises barriers to non-FTA members would be operating contrary to the core spirit of GATT 1994 and the WTO. It therefore follows that if they do not introduce more restrictive procedures, trade facilitation measures are of benefit to global trade.

Since trade facilitation involves cross border movement of goods, several measures would involve Customs. The fact that one of the core functions of an FTA is to facilitate trade means that Customs is at the centre stage and relevant. On this point, the role of Customs is synonymous with the operations of an FTA. This also explains the strong partnership between the WTO and the WCO in that both share a common goal of facilitating global trade. The preamble to the Convention Establishing a Customs Cooperation Council (WCO, 1950) also brings out that global customs cooperation was motivated by the need to support global trade following the signing of GATT 1947.

4.3. Elimination of duties

The term ‘FTA’ indicates free trade and consequently, the elimination of border-related taxes. The WTO uses the terms ‘duties’, ‘taxes’ and ‘customs duties’ interchangeably, and has a broad definition that these are taxes on imports and exports, which are levied as goods move across borders.[12] The WCO’s Harmonised System (HS) has been used as an instrument to allocate rates of duties and in implementing trade policy issues. From a broader perspective, it can be noted that the elimination of duties in FTAs is consistent with the objectives envisaged in the GATT 1994 which, in the preamble, refers to a desire for ‘the substantial reduction of tariffs and other barriers to trade’ (GATT, 1994). Whereas it is part of trade policy to identify goods that must be traded duty-free in an FTA, Customs becomes the relevant agency to interpret and implement what would have been agreed in an international agreement.

4.4. Elimination of other restrictive regulations of commerce

Apart from abolishing duties, an FTA must eliminate ‘other restrictive regulations of commerce’ (ORRC) in the constituent territories.[13] While ORRC is significant to the meaning of FTAs, and in enhancing trade among its parties, the meaning is not clear. Article XXIV is vague on the scope and coverage of ORRC. The other related term is ‘other regulations of commerce’ (ORC),[14] which is concerned with the elimination of barriers with third parties. ORC is discussed in Section 5.2 below.

It is obvious that ORRC cannot be referring to duties or tariffs because the reference to ORRC is preceded by the conjunction ‘and’, showing that this is an additional requirement to the ‘duties’ which are specified already.[15] The connection between ORRC and trade facilitation is referred to in the Understanding on the interpretation of Article XXIV of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, (WTO, 1994), which emphasises the internal liberalisation in FTAs and whose preamble reads:

[…] Recognizing also that such contribution is increased if the elimination between the constituent territories of duties and other restrictive regulations of commerce extends to all trade, and diminished if any major sector of trade is excluded;

Reaffirming that the purpose of such agreements should be to facilitate trade between the constituent territories and not to raise barriers to the trade of other Members […]

This then suggests that ORRC is all about the removal of restrictions affecting the cross-border movement of goods within the FTA such as administrative rules, trade facilitation issues or introducing burdensome surcharges and controls on intra-FTA trade. This view is corroborated by Lockhart and Mitchell (2005) who consider that the whole purpose of eliminating ORRC is, among others, to have a border-free FTA. Trachtman (2002) considers that ORRC is an internal test that calls for the removal of barriers to intra-FTA trade, whereas ORC [16] is concerned with the elimination of barriers with third parties. From the preamble to GATT 1994, it is clear that the agreement on trade in goods is directed towards liberalising ORRC. This was also raised in a WTO case of Turkey – Restrictions on Imports of Textile and Clothing Products, ORRC was broadly interpreted as relating to the movement of goods or the commerce within that particular FTA.[17]

Despite the vagueness in the interpretation of ORRC, from a simplistic point of view an FTA does not condone barriers to trade with both intra-FTA or third parties. The conclusion from this is that an FTA must not have restrictive laws or procedures for conducting business. As noted in Section 4.2 above, and as an example, Articles 3 and 4 of the AfCFTA Agreement is premised on removing restriction and liberalising trade. The elimination of ORRC in an FTA is therefore part of the process to liberalise trade in goods, and all these concern facilitating intra-FTA trade. Customs is a player in implementing some of the ORRC at the borders, and to some extent, in introducing some of the restrictive practices in international trade.

4.5. Liberalisation must be on substantially all the trade

One of the characteristics of an FTA is the requirement that liberalisation must be on substantially all the trade (SAT), and this also infers that not all products can be traded duty-free.[18] The adjective ‘substantial’ is judgemental and it invokes different meanings and understandings depending on the person measuring it and those affected by the value so determined. The interpretation of SAT is therefore not definitive and such flexibility creates room for disputes. The following extract from a WTO Appellate Body (AB) report in the case Turkey – Restrictions on Imports of Textile and Clothing Products demonstrates the difficulty in defining SAT:

Neither the GATT CONTRACTING PARTIES nor the WTO Members have ever reached an agreement on the interpretation of the term ‘substantially’ in this provision. It is clear, though, that ‘substantially all the trade’ is not the same as all the trade, and also that ‘substantially all the trade’ is something considerably more than merely some of the trade.[19]

While not providing any solution, the above statement merely restates the problem and demonstrates that there are no hard rules in the interpretation, and that each instance would be evaluated on its own merits. In a WTO case, US – Line Pipe, it was stated that NAFTA provided for the elimination, within ten years, of all duties on 97 per cent of the parties’ tariff lines, and that was more than 99 per cent of the volume of trade in the RTA.[20] Although the case did not involve Article XXIV, the panel was able to remark that such a figure was above the threshold of SAT. Despite not averting the opinion on SAT, the AB was to later observe that the question of Article XXIV was not pertinent to the argument.[21]

In a Working Party Report involving EC – Agreements with Portugal,[22] the EC argued its case that there was no specific definition of SAT, and while advocating for 80 per cent, it was reasoned that it was not appropriate to prescribe a figure. While Saurombe (2011) accepts these arguments on what substantial should encompass he observes, however, that the unsolved question is the attempt to define what must be excluded from SAT. In another case involving the EFTA, the Working Party argued that even with a figure of 90 per cent, that proposal could not be the only criterion for consideration.[23] The proponents of quality argue that SAT must be representative of a cross-section of all sectors involved in trade, and leaving out particular sectors goes against the spirit of Article XXIV that envisaged free circulation of qualifying goods in FTAs and CUs (Nsour, 2010). The qualitative approach is evident in that the word ‘substantial’ is describing ‘all trade.’ Based on the qualitative approach, the exclusion of a whole sector would therefore be contrary to the spirit of GATT.[24] Mathis and Breaton (2011) observed that, in practice, the quantity test based on approximately 90 per cent benchmark seems to be generally accepted as a viable indicator for several RTAs, however, it has been subjected to some verification using the test of quality. Although the issue has been debated within WTO jurisprudence, it is still subject to various interpretations and can therefore accommodate a variety of scenarios. There has never been a standardised method for determining the optimal level of SAT, and cases have varied depending on their background (Bhala, 2005). It has therefore been noted that, in view of this, the WTO continues to handle cases on their own merits (Matsushita et al., 2005).

Some customs administrations collect statistics on behalf of governments, while others proceed further to process trade statistics, and to that extent Customs becomes a useful agency in the chain and determining the various elements of SAT. The Harmonized Commodity Description and Coding System or the Harmonized System (HS), which is a customs tool, provides a useful framework to collect data, which can then be used to assess whether qualitative or quantitative trade is substantial or not.

4.6. Trade must be in respect of originating goods

Article XXIV:8(b) is clear that FTA members must grant each other concessions on products that originate within their borders. The rules of origin (ROO) can be viewed as the criteria to define the nationality of a commodity when it moves across borders. ROO exist because governments want to distinguish between foreign and domestic goods and, where necessary, accord preferential treatment (Falvey & Reed, 1998). ROO are an essential component in the operation of an FTA because their purpose is to ensure that the products granted free movement without payment of duty are those which have been defined as originating within the constituent territories of the FTA.[25] The criteria determining the ROO would be part of the FTA. This involves legally binding definitions of what is meant by originating products. The ROO are therefore important legal instruments for the application of preferential trade agreements. FTAs, such as SADC and the AfCFTA, have the rules as a separate annex or protocol, comprising an integral part of their respective agreements.

The application of such rules is critical because it prevents the FTA members from granting each other preferential treatment for goods sourced outside the continent. The rules therefore provide a control system to ensure that only qualifying goods enjoy the FTA preference. A typical annex on ROO would identify goods that must be wholly produced in a territory to qualify as ‘originating’ and this would be followed by other criteria such as the specific manufacturing or processing operation. Wholly produced goods are those which are wholly obtained, grown or harvested in a territory such as minerals, plants and animals. The second criterion applies to manufactured or assembled goods, as well as those made from materials obtained from a variety of countries including those outside the AfCFTA. This criterion has been difficult to interpret because it is intended to prevent the conferring of origin on goods that have undergone simple processes. The criterion involves technical expertise that must be defined by rules such as: the value addition test; the definition of substantial transformation; and requirements regarding change in tariff classification using the HS Code (LaNasa, 1996).

Free trade in an FTA is for qualifying goods as defined in the ROO. Therefore, an FTA must outline the processes for confirming the claimed origin of goods. Without enforcement measures, an FTA can end up trading in non-qualifying goods or products from non-members. Customs is an important agency to prevent fraud and ensure compliance with ROO by both importers and exporters. The need for skilled customs authorities and cooperation among the enforcement agents cannot be emphasised as this ensures proper implementation of agreed trade agreements.

5. External requirements for a free trade area

While Section 4 above discussed the constituent elements of an FTA, Article XXIV also imposes some rules on how members in an FTA must interact with each other in regulating their own trade. In addition to the requirements governing the intra-FTA liberalisation, Article XXIV also imposes certain obligations concerning how members of an FTA relate their trade with non-FTA members. An FTA has certain obligations that it must comply with or manage with outsiders or third parties. As noted, these requirements include a commitment by the FTA members not to increase trade barriers with non-FTA members belonging to the WTO, and a requirement that tariffs and ORC not be higher or more restrictive.

5.1. Trade barriers with non-free trade areas

It has been noted that while the purpose of an FTA is to facilitate trade among its members, WTO rules forbid FTA members from raising trade barriers against those WTO members not participating in the FTA. From Turkey – Restrictions on Imports of Textile and Clothing Products, two major conclusions were drawn regarding the relationships between FTAs and the WTO.[26] The first is that by removing trade restrictions and liberalising it, FTAs enhance the multilateral trading system. The second is that FTAs must generally be acknowledged as operating within the guidance and supremacy of WTO rules.

The WTO members who are not party to an FTA must therefore not be prejudiced by the actions of those who resolve to form their own ‘club’ within the bigger WTO family and agree to facilitate trade among themselves. At the same time, while facilitating intra-FTA trade, there is nothing to prevent FTA partners from reducing trade barriers by doing business with non-members of the FTA. As a result, an FTA must have either a neutral or an advantageous effect on non-members. In practice, non-FTA members might actually benefit from certain measures implemented within an FTA. For example, a measure to automate Customs procedures in the AfCFTA would accrue some benefits to non-AfCFTA members and global trade, as it would result in faster processing of all customs procedures without any discrimination.

5.2. Duties and other regulations of commerce

The relationship between the parties of an FTA and the members of the WTO not party to the FTA, in respect of duty concessions and ORC, is stipulated in Article XXIV: 5(b) as follows:

[…] the duties and other regulations of commerce maintained in each of the constituent territories and applicable at the formation of such free-trade area or the adoption of such interim agreement to the trade of contracting parties not included in such area or not parties to such agreement shall not be higher or more restrictive than the corresponding duties and other regulations of commerce existing in the same constituent territories prior to the formation of the free-trade area […]. (GATT, 1947)

From a common and general understanding, regulations to commerce affecting trading partners outside an FTA would include licensing requirements and border formalities. In a submission to the WTO by Korea it provided a list of some of the ORCs which were prevalent, including quantitative restrictions and measures of similar effect; Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT) and Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) standards; antidumping and countervailing measures; and ROO.[27] ORCs can therefore be interpreted to include trade facilitation instruments developed and implemented within FTAs.

The aim of an FTA is to enhance trade among its members and such a gesture among the participating members must not prejudice non-FTA members. Saurombe (2011) underscores the point that this is in line with the notion that Article XXIV’s primary objective was not to make FTAs a barrier to the growth of multilateral trade, but rather to make them a step towards free trade. Consequently, while entering into an FTA, the members must not alter their external trade policies in such a manner that they negatively impact WTO members who are not party to the FTA. It also implies that, when trading with non-members, FTA members would either maintain or reduce tariffs and not raise any trade barriers found in place. In practice, chances are that tariffs involving external trade members of the WTO will gradually be reduced in line with continuous obligations under multilateral trade negotiations. The formation of FTAs, in effect, assures non-members that their tariffs and ORCs have been bound and will not exceed what they were prior to the formation of such an FTA. Customs is therefore placed at the centre to ensure that global trade is in line with GATT rules.

6. Conclusion

Article XXIV has important provisions in international trade law in that it allows for exceptions from the most favoured nation (MFN) principle. It provides for the formation of FTAs and allows them to operate outside the MFN rule. Article XXIV defines an FTA and provides rules governing its operations. Article XXIV therefore permits a coalition of certain members of the WTO to cooperate and extend to each other preferential treatment not accorded to every other member of the WTO. Therefore, FTAs may develop their own legal instruments to liberalise and facilitate trade among their own members. An FTA can therefore legitimately implement more favourable trade facilitation measures if it does not impose additional trade barriers on third parties.

This paper has demonstrated the relevance of Customs in FTAs. The definition itself is comprised of customs and trade-related terms such as customs territories, elimination of customs duties, rules of origin and trade facilitation matters. An FTA represents a liberalised trading regime in respect of qualifying goods. Customs stands at the centre of trade facilitation and the movement of goods across borders and to ensure compliance with the rules agreed by the parties to the FTA. Customs is therefore obliged to ensure that it implements the agreed trade facilitation measures. It is also expected to cooperate to ensure that the movement of goods is not delayed. As such customs administrations play a major role in ensuring the success of an FTA.

Using the definition given by the WCO in the Glossary of International Customs Terms (WCO, 2013), Customs is the governmental agency mandated with enforcing various laws and rules pertaining to the import, export and transit of goods as well as the administration of customs legislation and the collection of tariffs and taxes.

Apart from Customs, some of the players involved include other government departments such as agriculture, foreign trade and the banking sector.

For example, the definition in WTO (n.d.).

The exceptions in Articles XI, XII, XIII, XIV, XV and XX with quantitative restrictions; balance of payments; exceptions to the rule of non-discrimination; exchange control arrangements; and general exceptions.

WTO Decision of 14 December 2006 on Transparency Mechanism for Regional Trade Agreements (18 December 2006) WT/L/671.

WTO General Council Decision of 14 December 2010 on Transparency Mechanism for Preferential Trade Arrangements (16 December 2010) WT/L/806.

WTO Agreement Art XVI: Explanatory Notes (GATT, 1994) reads: ‘The terms “country” or “countries” as used in this Agreement and the Multilateral Trade Agreements are to be understood to include any separate customs territory Member of the WTO.’

Cottier, T. and Nadakavukaren Schefer, K. (1998, February). Legal opinion submitted to the economic policy programme on conditions and requirements to qualify as a separate customs territory under WTO rules. EPPI C5.

US Department of State, Existing US trade agreements, https://www.state.gov/trade-agreements/existing-u-s-trade-agreements/, accessed 13 August 2022.

Agreement Establishing the African Continental Free Trade Area (adopted 21 March 2018 (entered into force 30 May 2019) art. 3 and 4. https://au.int/sites/default/files/treaties/36437-treaty-consolidated_text_on_cfta_-_en.pdf

AfCFTA Agreement, p. 17. Protocol on Trade in Goods (adopted 21 March 2018, entered into force 30 May 2020).

WTO. Understanding the WTO, The Agreements: Tariffs: More Bindings and Closer to Zero, https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/whatis_e/tif_e/agrm2_e.htm, accessed 21 April 2021.

GATT 1994 Art XXIV:8(b).

ORC is stipulated in GATT 1994 Art XXIV:5(b).

GATT 1994 Art XXIV:8(b).

ORC is stipulated in GATT 1994 Art XXIV:5(b).

Turkey – Restrictions on Imports of Textile and Clothing Products: Report of the Appellate Body (22 October 1999) WT/DS34/AB/R [48].

GATT 1994 Art XXIV:8(b).

Turkey – Restrictions on Imports of Textile and Clothing Products: Report of the Appellate Body (22 October 1999) WT/DS34/AB/R [48]. https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/FE_Search/FE_S_S006.aspx?Query=(@Symbol=%20wt/ds34/ab/r*%20not%20rw*)&Language=ENGLISH&Context=FomerScriptedSearch&languageUIChanged=true#

US – Line Pipe: Report of the Panel (29 October 2001) WT/DS202/R [7.142]. The case was in respect of safeguard measures under GATT 1994 Articles I, XIII and XIV.

US – Line Pipe: Report of the Appellate Body (15 February 2002) WT/DS202/AB/R [199].

GATT Working Party Report on EEC, GATT Doc BISD 20S/171 para 16.

GATT Working Party Report on EEFT, GATT Doc BISD 96/83 para 48.

WTO, Committee on Regional Trade Agreements: Annotated Checklist of Systemic Issues – Note by the Secretariat (26 May 1997) WTO Doc WT/REG/W/16 paras 40–44.

AU, UNECA and AfDB (2017). Assessing Regional Integration in Africa VIII: Bringing the Continental Free Trade Area About. UNECA.

Turkey – Restrictions on Imports of Textile and Clothing Products: Report of the Panel (22 October 1999) WT/DS34/AB/R [9.163].

WTO. Negotiating Group on Rules of Origin, Submission on Regional Trade Agreements: Communication from the Republic of Korea (11 June 2003), WTO Doc TN/RL/W/116.